Dive into the highly-stylized, sensuous portraits of women by the 20th century painter Tamara de Lempika. Special thanks to the scholarly text “Tamara de Lempicka: Art Deco Icon,” by Alain Blondel.

.

“Self Portrait in a Green Bugatti,” 1929

Script: Episode 127: Tamara de Lempicka: Desire and Seduction in Portraiture

Hello my art enthusiasts! Recently I came across a quote by the painter and portrait artist Alice Neel. She is known for her expressionistic and emotionally intense portrayals of people. She said, “Art is two things; a search for a road and a search for freedom.”

As the spectator, a friendly reminder, I am an art historian, not a studio artist, I am visually on the receiving side of the canvas, within that intimate space between myself and a work of art, this is where I search “for a road” and for freedom— freedom from constraint. Neel crystallized or articulated more clearly, more succinctly in that quote what I have been doing since the moment I first experienced art in my very young twenties. Currently I am knee deep in writing a memoir that explores the ways art impacted my life on so many levels and truly liberated me intellectually, emotionally, even spiritually. But that quote from Neel—she continued saying “you know all these things in life keep crawling over you all the time, so it’s very hard to feel free.” It inspired me to rethink the format of this podcast show. It tickled my curiosity to learn from the women artists I engage with, celebrate in this show, to dive deeper–In their artistic practice, in their creative life—what road or roads are they seeking and what does “freedom” look like for them—how do they communicate that in their art? Today’s episode focuses on a female artist from the early 20th century, Tamara de Lempicka—but in upcoming episodes later this summer and into the fall and I have a exciting roster of artists including painter Deborah Wasserman, sculptor Melanie Pennington, muralist Jenie Gao, illustrator Laerta Premto and a revisit on the installation artist Kathryn Hart, –I hope to include and engage with them in our conversations Neel’s quote—what is the truth from their own journey are they telling us through their art? I have the honor of sharing at least from my perspective how what they do benefits and impacts the world.

If you would like to participate in an episode, be included in my conversation with an artist, either on air or prepare questions, please visit my Patreon: Beyond the Paint with Bernadine to learn more—check out The Pindell in honor of the painter Howardena Pindell membership tier. In my last episode (#126) I had this wonderful conversation with the portrait painter Ruth Bullock who gave me a much needed and deeper awareness of the lack of representation in the visual arts of Trans people. I am a perpetual student and learn so much from other artists and art enthusiasts like you. It would be just cool to have someone from my audience to engage or be a part of it. You can also contact me at Bernadine@beyondthepaint.net. Thank you!

Let’s turn our attention to the female artist Tamara de Lempicka, diving into one of her iconic works, an image of a white woman, whose gaze at the viewer is cool and unflinching. She wears a flowing sage green scarf with a matching closely fitted cap that reveals a ringlet of her blonde hair. She exudes a fiery beauty with her vivid red lipstick as her brown-gloved hands rests on the wheel of a Bugatti. “Self Portrait in a Green Bugatti” (oil on panel-1929), a highly stylized self-portrait that exemplifies aesthetically the Art Deco or Art Nouveau era. The portrait was created for the cover of a German fashion magazine-De Lempicka exudes independence and inaccessible beauty. For a moment consider that this portrait, this image, was mass produced for Die Dame, a German magazine devoted to promoting the concept of the modern woman—think about the access that image had for woman, de Lempicka painted, illustrated using herself as the model or sitter, “the New Woman of the Roaring 20s”—a feminist ideal and reaction against Victorian womanhood–those long-held notions of femininity and the proper social sphere, mostly relegated to the domestic sphere for women—The New Woman was free-spirited, independent, educated and uninterested in marriage and children. “Self Portrait in a Green Bugatti” is emblematic of the New Woman, the painting, like many of her other portraits of women, contain narratives of desire, seduction, modern sensuality. What she accomplishes in her portrait is to paint an amplified version of reality.

Let’s also put this painting, this work into another context-within the Art Nouveau aesthetic. Art Nouveau, French for “new art” It was the visual style of the late 19th and early 20th century, roughly 1890s to the start of World War I in 1914.

This was a time of great social change in Europe. A growing middle class had sufficient income to enjoy the pleasures that life had to offer. As they faced the new century, however, some were anxious (and rightly, in view of the war that ensued a decade later) about the changes it would bring. In art and design, the Art Nouveau style emphasized decorative pattern and applied it to the traditional “fine arts” (such as painting and sculpture), the decorative arts (such as furniture, glass and ceramics) and architecture and interior design. Art Nouveau is characterized by organic flowing lines, gold decoration and the simulation of forms in nature. (Organic: having irregular forms and shapes, as though derived from living organisms)

The Belgian architect Victor Horta designed a home for Emile Tassel infused with elements that would come to epitomize Art Nouveau. Horta utilized new, modern materials, such as cast steel and glass. He created a home in which form and light seem to be in constant emotion, even alive like the organic forms that inspired him. The elegant staircase twists like a roller coaster and widens as it spills onto the floor. Further spirals flood the walls and the mosaic floor, creating an eternally active space.

Louis Comfort Tiffany brought Art Nouveau to America with works whose designs derived from complex forms found in nature –a beautiful example is his “Wisteria” lamp from 1905 made from leaded glass

Tamara de Lempika is the first one to apply this aesthetic to the canvas. Her paintings as I noted often contained narratives of desire, seduction, and modern sensuality, making them revolutionary for their time. Her style, her portraits of women exuding independence and inaccessible beauty, “in many ways have been assessed as inseparable from her larger-than-life character—she constructed a personal persona and was a canny self-promoter, “self-styled experimental artist and astute cultural and historical prognosticator, that truly engaged her audience, some say even more significantly than her gender.” (the art story)

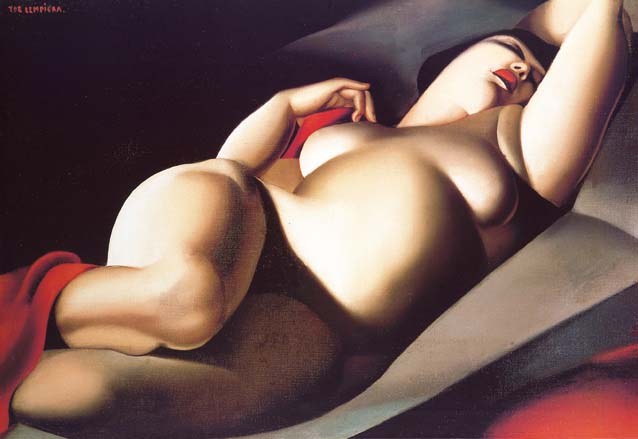

Another subject of De Lempicka’s works was her luscious nudes were based on models with solid, strong – yet feminine – figures. Filled with elegance, nonchalance and erotic appeal, they suggest the sensuality and vitality of the circles in which the artist moved. De Lempicka’s sitters’ and this includes clothed women, were often dramatically lit and showcased in closely cropped compositions so that they filled the canvas with a powerful, monumental presence.

La Bella Rafaela is a reclining nude but the power and sensuality of this image is in the sculptural form of the nude figure. The shapely curves of the model “Rafaela,” it is said Lempicka found her in a very large park where prostitutes often proffered their services, have both a beauty and strength—Rafaela became the artist’s main muse for over a year. La Bella Rafaella catches our attention with her pose, she is voluptuous, self-confident nakedness—“The figure itself is composed of weighty, plastic forms, her sharply outlined musculature swells in the highs and lows of a dramatic lighting—reminiscent of a Caravaggio painting. Her lips are glowing red, the background is black, teasing scarlet red drapery partially covers one breast and her part of her muscular legs—the floor a milder echo of red and in between the drapery and floor is a tonal beige couch in which the body, cat like, sinks into. Her beauty is highly stylized, inaccessible yet tauntingly coy. The bodies, their forms do straddle between the curvaceous and the vocabulary of Cubism which makes use of simple geometric shapes, interlocking planes in constructing or building up form. Lempicka both absorbs tradition yet invoked a modernist aesthetic.

“The female body occupies a central position in de Lempicka’s work—at the time “the act of painting one’s own body, or that of a nude woman became a declaration of one’s own self-determination as a woman. Contemporary women like Suzanne Valadon and Paula Modersohn-Becker explored the nude figure through self-imagery—Modersohn-Becker painted her mostly nude, pregnant body wearing brown glass beads around her neck. In its time the nude figure painted by women was still considered taboo.

She was a master of theatricality. One of her teachers were the cinema, the performing medium of her age with stars like Greta Garbo and Mae West, both “glamorous vamps.” De Lempicka borrowed their looks and demeanor for her subjects. We can see the deep emotion from characters of the cinema in the women she portrayed. In our looking experience, we become locked into an isolated cocoon drawn more deeply into varying levels of the sitter’s inner life. Why I am so captured by de Lempicka’s women. I leave you with another example of her work—I am knee deep in writing a memoir about the impact of visual imagery and art in my life—many of my earliest influences, I grew up Catholic, were religious icons, especially Virgin Mary. In the mid-1930s de Lempicka suffered from depression and “her mental affliction slowed her production considerably. Such was her distress that only religious subjects had any meaning for her. She painted several young Madonnas with pure oval faces. She did make a number of replicas and compositions inspired by paintings she had seen in museums or in books. In the work Madonnna, 1937, we a close up of the face of a young Virgin Mary. Her head is covered in white veil, her face steady with its chiseled features, the style points to Art Deco, her blue eyes gaze towards the Heavens. Her sculptured cheekbones and blushed lips hold this beauty, yet there is solidity in her demeanor that illuminates the Mother of God’s inner strength, dare I say boldness. Like her self portrait, behind the wheel of a Bugatti, both images are elegant and feminine yet boldly portray aspects of women’s independence and purpose.

Thank you for listening Resources and images highlighted for this podcast, and I am indebted to the text Tamara de Lempicka: Art Deco Icon is on my website @beyondthepaint.net. Please follow me for more engaging content about women artists on IG @beyondthepaintwbernadine—links are in the podcast notes.