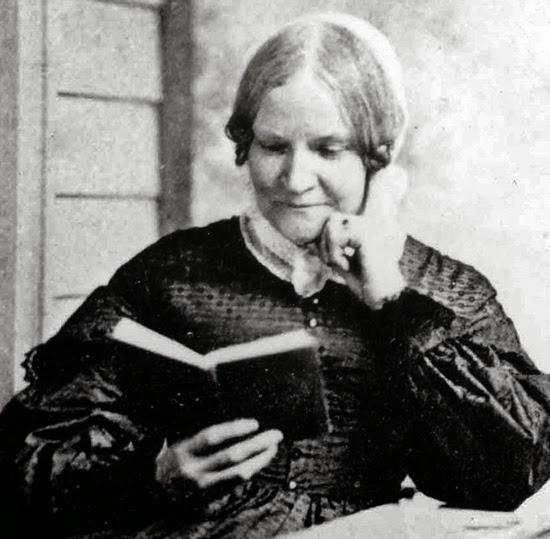

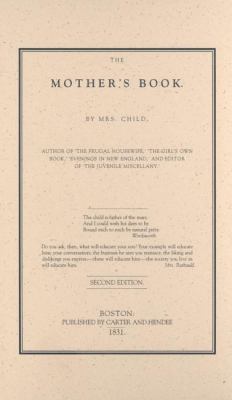

The private feelings of motherhood as expressed by Millicent Leib Hunt when she realized she was pregnant for the fifth time, offers me a compelling insight of the early 19th century woman. “Yes even now the frail foetus within me is the abode of an immortal spirit, and this has caused thoughts of discontent, I would it were not thus, I love my liberty, my ease, my comfort and do not willingly endure the inconvenience and sufferings of pregnancy and childbirth.” The constant cycle and often high frequency of pregnancies and births for women, who could not control conception with certainty, posed deep anxieties. Above and beyond the loss and grief of young children highly vulnerable to disease and household accidents, Millicent’s passage mirrors the expected role of motherhood as a vehicle for the child’s growth versus the cultivation of the mother-child relationship. Self-fulfillment for many women did not configure into the raising of children which required the “habitual command over one’s own passions.” Lydia Maria Child in her Mother’s Book further warns women, “The care of children requires a great many sacrifices, and a great deal of self-denial, but the woman who is not willing to sacrifice a good deal in such a cause does not deserve to be a mother.”

My long-held assumption of the early 19th century American mother, her predetermined embrace for the maternal is put into question. To be honest, I find this refreshing! Women of this era, like some women of today, “struggled” between personal longings and the expectations of role as mothers. I am simplifying my assertion within the limited space of this blogpost, but my readings of the Millicent Leib-Hunt and Lydia Maria Child passages do stir my curiosity in the context of Elizabeth Colt. Did child-rearing attitudes and expectations, the apprehensions felt by women like Millicent Leib Hunt cross over the threshold of wealthy Elizabeth Colt’s “ideal” of motherhood? A woman who spent years of her life and money building memorials and collecting and commissioning works of art to honor and memorialize the loss of her husband Sam and children. Another New Englander, Susan Huntington wrote in her diary in 1813, “The idea of soon giving birth to my third child and consequent duties I shall be called to discharge distresses me so I feel as if I should sink.” Perhaps there was a part of Elizabeth that carried apprehensions in her role as a mother beneath the tide of her personal longings.

Resources for this blog post include Nancy F. Cott, “The Bonds of Womanhood,” and Sara M. Evans, “Born of Liberty.”