My book centered on the contributions of the arts by Elizabeth Colt will share a focus on the emergence of pictorial art by women in Hartford. Elizabeth commissioned paintings and sculptures alongside collecting works in her travels. She engaged with established artists like Frederic Church and Albert Bierstadt. In Connecticut’s early history, two-dimensional art emerged in 1762; the first documented painter in the region was William Johnston.

What I find compelling is that two decades earlier, Connecticut women created pictures on canvas. Unlike the paintings by William Johnston who applied pigments with a brush, women created visual compositions (assemblages of color, line and iconography) with polychrome fibers and a needle. Connecticut needlework, dating to the decade of the 1740s, included floral patterns, ambitious pictorial compositions that incorporated buildings, animals, trees, figures. In this blog post I want to highlight the work by Miranda Robinson (1831-1903) and her accomplished decorative work, a 1839 Sampler completed when she was eight years old. It is also a rare example of work by a black girl, born in Connecticut by free, literate blacks in a moderately prosperous household. Her connection to Elizabeth Colt? She and her younger brother George were employed by the Colts in their Hartford home.

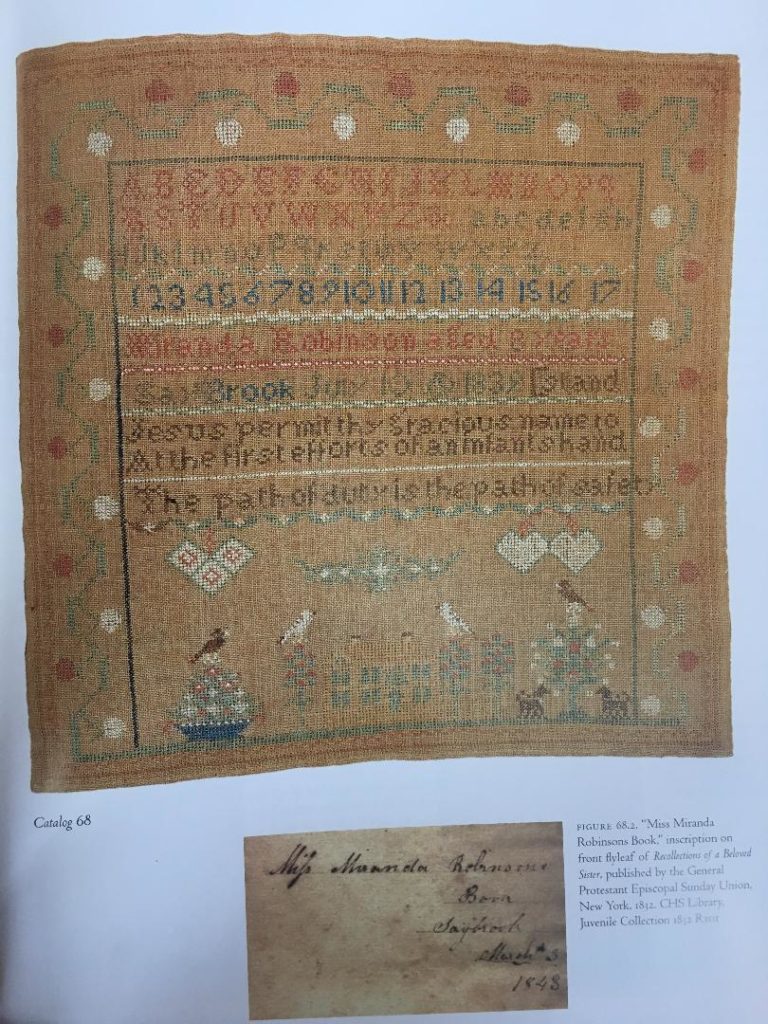

Miranda preserved Sampler is in the collection at the Connecticut Historical Society and highlighted in a wonderful resource and book by Susan P. Schoelwer, “Connecticut Needlework: Women, Art, Family 1740-1840. Schoelwer writes, “Miranda’s work is typical of contemporary Connecticut samplers, demonstrating its maker’s acquaintance with both traditional forms and current fashions, as well as her access to the necessary instruction, skills and materials.“ It includes two upper and lower case alphabets, numbers, signature, text, strawberry vine borders, hearts, stylized flowers and trees and small landscape vignette within a palette of single tones of red, white, green and tan.

I am especially enthusiastic in my immersion into decorative needlework because these compositions remained largely outside early American Art History. To our modern eyes, saturated in imagery, these works may appear primitive or unpolished. I think you will agree and I hope to underscore in the book, the patterns of expression produced with textile materials and techniques illuminate aspects of the woman who created them.