I celebrate two perspectives of the female body through the artistic visions of two 20th century, Latin American artists: Zilia Sanchez and Tarsila do Amaral. What I hope for you in this episode is to embrace the artistic pathways both these female artists took in finding their own artistic voices; transferring it through new ways of seeing the female body. Let’s dive in….

Resources for this podcast episode include the writings of Natasha Moura, Joyce Beckenstein, Alex Pilcher, Alexxa Gohardt, Dr Maya Jimenez, Museum of Modern Art, Art Institute of Chicago and curator/historian Luis Perez-Oramas.

Episode 103: Script

Hi my art enthusiasts! Before we dive into this week’s episode, I want to share with you an art history podcast I recently discovered: Stuff About Things: an Art History Podcast, hosted by art historian Lindsay Sheedy. Her perspective in the world of art is so much fun and she offers multiple perspectives on objects of art that challenge artistic traditions. My favorite episode is —-#23 on the contemporary painter Kehinde Wiley. I reached out to Lindsay and had a lovely email exchange. We discussed collaborating on an upcoming episode possibly in March. Stay tuned for that. In the meantime, I hope you will check her out. I put a link to her series in the podcast notes. Thank you!

And welcome to Episode 103: I present two views of the female body through the artistic vision of two Latin American artists: Zilia Sanchez and Tarsila do Amaral. They are both 20th century artists, Tarsila from earlier part of the 20th century working through the Modern era and Zilia, born in 1947 was exposed to Modernism but in her travels from Cuba to Spain and then in New York in the 1960s she was shaped by Minimalists. What I hope for you to embrace in both Tarsila and Zilia are the artistic pathways they took in finding their own artistic voices and visions, creating works outside of the artistic traditions of Western art. Let’s dive in…..

My celebration begins with Zilia Sanchez

I came across a compelling question by the art historian Alex Pilcher: Can the visual language of minimal, abstract forms articulate the sensual interactions between human bodies? This question peaked my curiosity for the enthusiasm I have for the figure, especially the female body. In this podcast series, I have explored and journeyed with you the female figure through paintings, photographs, prints–experiencing the body, the nude body in its natural form. Pilcher’s question led me to the work and artistic practice of Cuban born artist Zilia Sanchez.

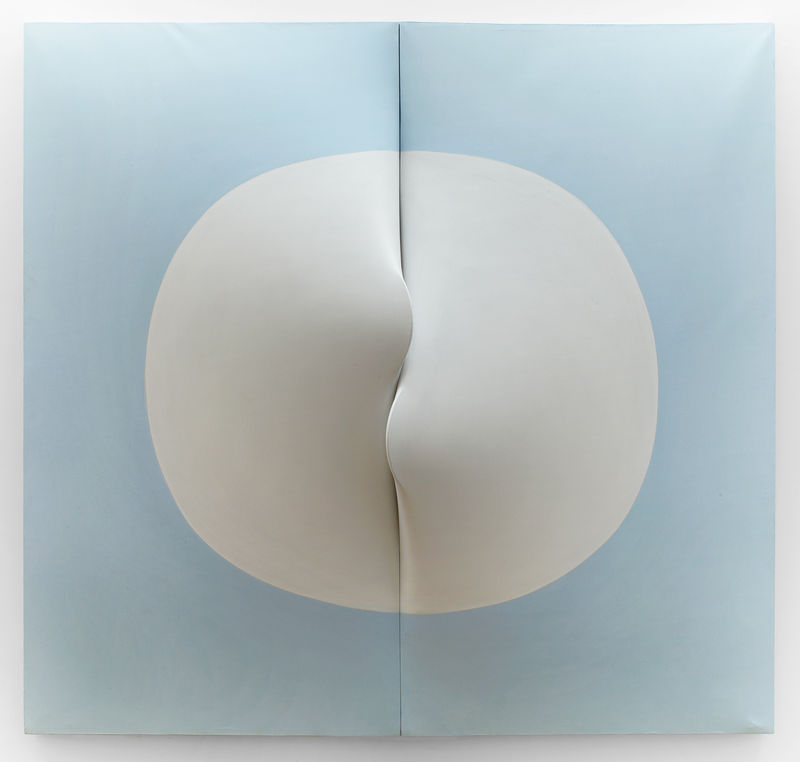

Her work is a hybrid between painting and sculpture characterized by “her distinctive approach to formal abstraction, undulating silhouettes, muted color palettes and a personal sensual language.” Before we unpack the elements within her work, let’s journey through one of her hybrid paintings from 1973: Lunar V.

The painting is a stretched canvas layered with three dimensional protrusions or shapes; elements that recall the contour of female parts. Her color palette is minimal white and blue, I would describe the blue hue as a sky blue. Sanchez stretched the canvas in such a way as to create the protrusions or projections resembling interlocking tongues. There is also an interpretation the protrusions resemble labia. The overall shape of the contoured, white surface is round, the center is sliced like two halves of a full moon tapered into tongue-like crests which interlock and extend toward the viewer. The appearance of the body parts, is very precise, hard-edged, non-figurative, devoid of the aesthetics of the tongue’s or labia’s surface. What we see in her undulating silhouette, is Sanchez’s personal sensual language. She abbreviates the female form; our view, our experience distilled into the formal elements of color, line, shape.

Lunar V and other works in this series was (from Art in America magazine) “crafted in the wake of the Apollo moon landings and the resurgence of the feminist movement in America. Lunar V suggests both the female anatomy and the celestial terrain at a time when women’s bodies and outer space were contest sites of mythic possibility. Women’s bodies were subject to processes of domestic control, the lunar world to geopolitical control.”

In the erotic overtones of the contours of female body parts in Sanchez’s canvases (they range in scale from intimate to monumental), the body’s warmth is “disrupted by Sanchez’s cold-like and impersonal approach to the body.” What Sanchez invites us to experience “is a reading of the female anatomy evocative of the topography of celestial bodies.” The title Lunar implies the moon.

The artist herself describes them as “erotic topologies.” Through a restricted vocabulary, some describe as clinical, Sanchez associates the body, specific female body parts like the breast or labia purely on the surface. We do not see the resemblances of flesh–instead we see the very top surface through “immaculate paint choices.” Her paint is flawlessly hard edged, drawn from a palette of cool shades, the maximum in this series is four tones, white, grey, blue, the palest pink. As we see in Lunar V, she draws from just two; white and blue. What is erotic or sensual in the work is the tension between the two parts, the pressing of the two interlocking lips. We are not invited to observe an explicit image; instead we partake in this wondrous relationship between the grounding of the female body and the celestial bodies. Through Minimalism, Sanchez developed a distinct language of sensuality in the embrace of the curve in her works. Minimalism was a mid-20th century art movement, practiced primarily in the United States. As the name implies, Minimalist art is pared down to the “minimum.” Its goal is to reduce painting and sculpture to essentials; the bare-bones essentials, eliminating any representational imagery, including as we see in Sanchez’s work, the artist’s touch–all gestural marks eliminated.

She arrived at her unique shaped-canvas process by chance: From the writer Joyce Beckenstein, “While sitting on her roof deck she one day noticed a sheet on a clothesline whipped by the wind, wrapping itself around a nearby pipe. The sight inspired her odd shaped canvases.

Another example is “Topologia Erotica,” from 1968. It consists of a single breast-like form with a separation—suggesting a division into a pair of breasts with a projecting button-like “nipple.” Suspended above a small oval with double “buttons,” it hovers over the smaller form like a protective biomorphic mother. Such meanings and associations are subject to highly personal interpretations, prompting Holland Cotter to write: “Altogether there is nothing in New York galleries like this work, which has a boldness and strangeness entirely its own. Why we have had to wait so long to have a survey is a mystery.”

Sanchez took her cues from European Modernism–abstraction and later Minimalism. Modernists were her role models rejecting the traditional curriculum taught at Escuela Nacioinale de Belle Artes where she graduated in 1942. She was innovative with a rebellious spirit and through a grant to study in Spain, she went on to New York where she studied at Pratt Institute. Here is where she witnessed the most strident years of the feminist revolution. Though when asked about the impact feminism had on the artist she replied, ” I was exposed to the movement but was not following it closely.” Unlike female artists Carolee Schneemann who identified as feminist, who saught in feminism’s early days to reclaim the female body and to confront its objectification through the male gaze, Sanchez does not see herself in that role.

Even though Sanchez rubbed shoulders with Minimalism she noted, “I’m not sure if I was influenced, but I did like the work of Eva Hesse and Lucio Fontana…. I don’t think my work falls within the style of any artist.” She refers to herself as a “ Minimalist Mulata”—one who adopts her cultural and gender history to the spare and pared down geometries that dominated the sixties. But in doing so, she underscores that her own work always included imagery related to the female body. It is through the layering of experiences, and practices, coupled with extraordinary innovation with art’s formal language she found her personal voice. She permanently moved to Puerto Rico in the early 1970s where she continues to work well into her 90s. Her work is seldom seen outside of Puerto Rico and another reason for me to amplify her voice and the ways her evocative works can engage us to see the erotic and the sensual through a minimalist lens.

In this episode I am introducing you or highlighting examples of female Latin American artists. Latin American artists, a term coined in the 19th century–from the historian Dr Maya Jimenez “broadly refers to the countries in the Americas (including the Caribbean) whose national language is derived from Latin. These include countries where the languages of Spanish, Portuguese, and French are spoken. Latin American is therefore a historical term rooted in the colonial era, when these languages were introduced to the area by their respective European colonizers. “

Ask an average person to name a Latin American woman artist, and they will most likely mention Frida Kahlo. There is no disputing Kahlo’s place in the art historical canon; she was a master of the self-portrait. But even she, as writer Alexxa Gotthardt so eloquently claims, “confronted hurdles on her journey into history books and popular consciousness…including the flagrant marginalization Kahlo faced as both a female and Latin American artist.” It is truly unacceptable to segregate and exclude women and Latin American artists in the canon of art. In the 21st century we are witnessing a shift in the narrative of the story of art as museum collections like the Museum of Modern Art in 2018 reconfigured their galleries, shattering the chronological spine to amplify a broader range of voices.

Latin American women like Brazilian artist Tarsila dol Amaral, a daughter of the coffee-planting aristocracy who studied art in Europe, shaped by Modernist Cubists Fernand Leger and rubbed elbows with Pablo Picasso and sculptor Constantine Brancusi. In her canvases she brought from these giant figures of Modernism, elements of their modernist paintings; flattened forms, fractured space, distorted bodies–back to Brazil.

And like Sanchez made them her own by “including content ignored by her European counterparts. She filled her canvases with vibrant scenes of Brazilian life, and the powerful, abundant bodies of female figures.” She helped to define a new, uniquely Brazilian style by “cannibalizing” defining aspects of Western art.

Like Sanchez, her early work is academic; her transformative moment is her return from Europe where she rediscovers her own country, creating new pathways in modernism. Art historian describes it as a “moment of compassion for specificity of her own country.” She was a part of a small group who was in constant relationships with the avant garde artists in Europe. She pushed the boundaries of Brazilian modern art by ingesting and transforming sources; first from Europe and then from her own country. She made a radical statement unlike any Brazilian artist before. She said, “I wanted to make something really out of the ordinary.” Her signature figures of female bodies are monstrous. Her paintings are radical in their depiction of the female form. She describes them composed of “little heads, skinny arms supported by an elbow with enormous long legs and feet.” She mixes European modernism and surrealism with local colors, themes and forms. Her paintings though strikingly modern communicate the essence of the Brazilian landscapes (real or fantastical.)

My favorite and I think one of the most iconic of her paintings is the 1928 work, “Abaporu,” Created for her husband the poet Oswalde de Andrade, the painting depicts an elongated, isolated figure with a blooming cactus. From the writer Natasha Moura, “the word abaporu comes from the Tupi language (the language from most important indigenous people of Brazil) that means “the man that eats people” aba (man) plus poro (people) plus u (to eat). The artist described the painting as a “monstrous solitary figure, enormous feet, sitting on a green plain, the hand supporting the featherweight miniscule head. In front of a cactus exploding an absurd flower.” What captures my attention as indicated by the artist is the exaggerated, distorted body, dominated by the feet, the head so small with no defining features. Her body is ageless, sexless, undressed against a landscape of deep green grass beneath her, the erect cactus and ball of light from a golden sun sits like a crown atop a blue sky.

Tarsila do Amaral and Zilia Sanchez, two Latin American female artists, both dominated by artistic traditions, find their own voices by adopting their own versions of Modern and Post-Modern art drawn from their travels and engagement with European and American avant garde. They literally gobble up these traditions, digest them and then translate onto the canvas their own versions, their own visions of the female body. From the vibrant colors and expansive, exaggerated forms of Amaral’s bodies to the impersonal approach of Sanchez’s abstracted female body parts, we are immersed through the exterior, the interior selves of these two remarkable women artists.