Artist Peter Bustin loves to “paint humans.” He sees beauty in all people and he encapsulates that love and admiration through layers of paint like a sculptor forming a figure in clay.

I came to know Peter and his work through this show. Join me and learn why I broke with my show’s tradition of celebrating women artists, to celebrate a male one. 🙂

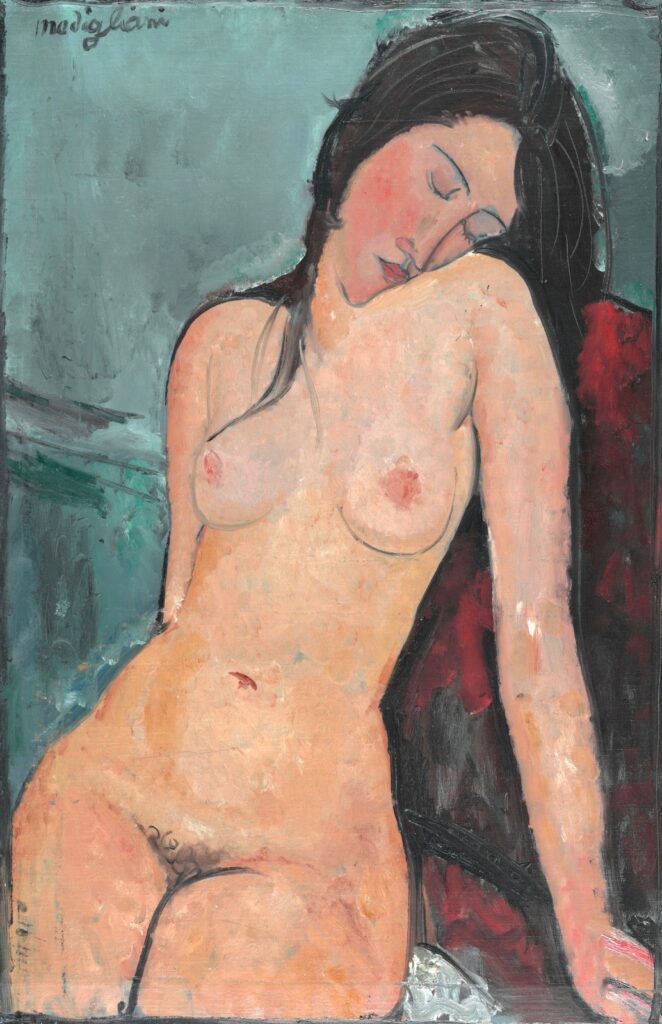

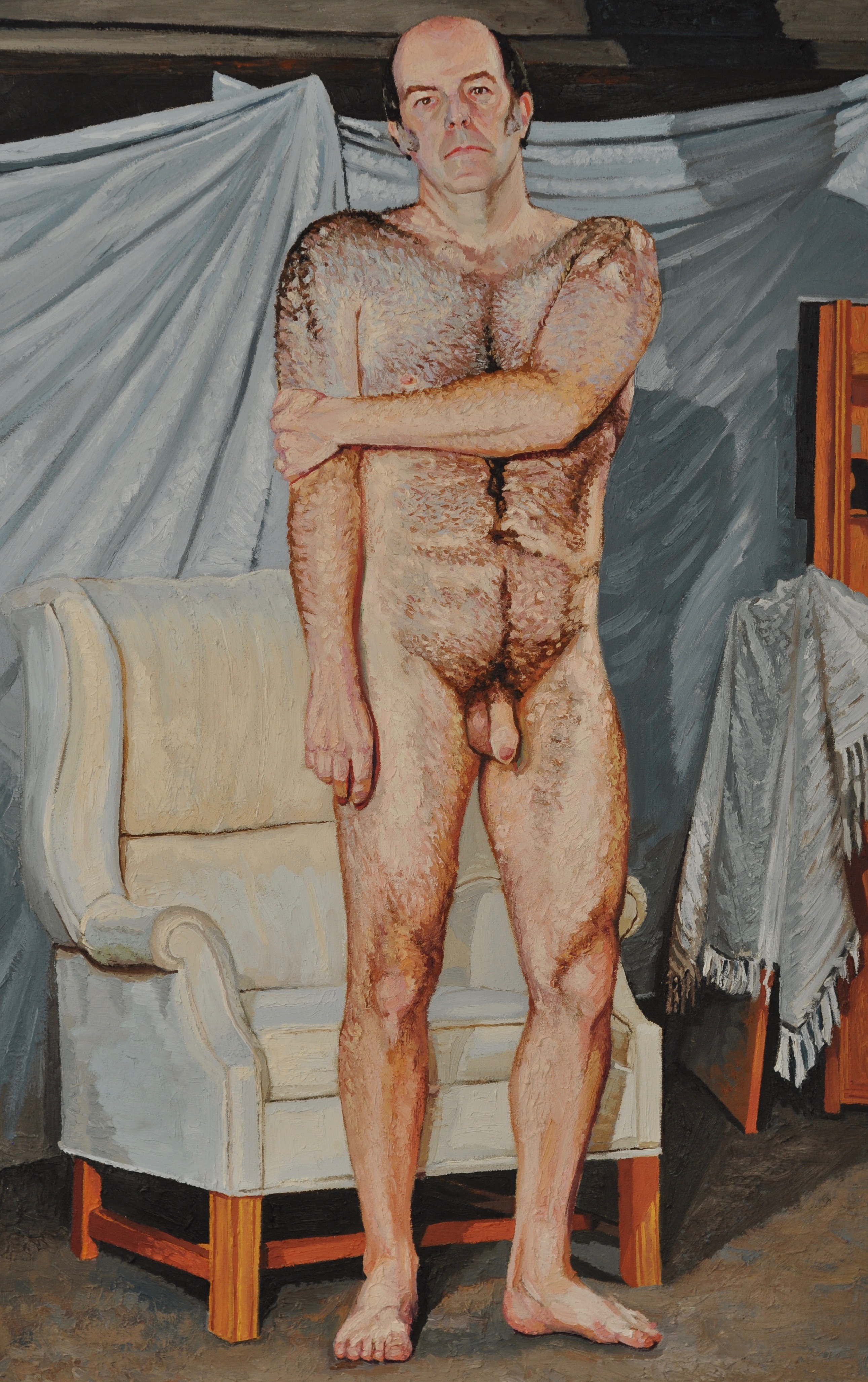

Works discussed in this episode include (listed in order as shown below), Peter Bustin, “Naked,” and “H. Modigliani.” Influences of Peter’s work include portraits by Alice Neel (“Self-Portrait, 80”), Rubens wife, (“Helene Fourment in a Fur Robe”), and Amedeo Modigliani (“Female Nude, 1916”)

Resources include Tate Museum, Widewalls Magazine, the writings of Debra J. DeWitte, M. Kathryn Shields, Ralph M. Larmann, Susie Hodge and the curator Dr. Barnaby Wright. I encourage you to follow Peter on Instagram @peterbustinartist

Script: Beyond the Paint the podcast, an audio journey into the voices of women artists and their contributions to the story of art is celebrating a contemporary male artist–Yes, I am breaking away from my own traditions of this show with the contemporary artist Peter Bustin from New Foundland. My dive into his paintings of primarily female nude figures and his nude self-portrait is inspired through a friendship I developed with Peter through this series. Yes–Peter a listener has engaged with me in conversations outside of the podcast series about the contributions of women and the ways she represents and portrays the female figure. It is one of the joys of my podcast–you get to meet and engage with artists and like-minded folks like you my listeners.

Peter is also my guest and in a bit you can listen in on a conversation we recorded about his work. and artistic practice. Peter loves to “paint humans.” He sees beauty in all people and he encapsulates that love and admiration onto the canvas. As we will see in his works, he forms the body through layers of paint like a sculptor forming a figure in clay. What we see, what we feel so tangibly is the texture and color of skin and his innate attention to the surface of the body. Through his brushstrokes, both loose and defined–we experience the markings, meticulous details of the body, that form the person. The result? Eloquent and exquisitely crafted bodies.

Before we dive into Peter’s singular works, let’s think about the representation of the body, the human form in art, –a bird’s eye view of its history. We will experience it through painting, exploring the figure on a two dimensional surface. (canvas, or on a pot, a wall) “The human figure is one of the most common subjects in art, perhaps because making art about the body allow us to reflect on, come to terms with , and literally express ourselves. For thousands of years, the human figure has appeared in art. Early cave paintings show figures of hunters depicted through a few strokes. In ancient Greece human figures were the main subject on decorated vases. In ancient Rome, compositions of figures filled the walls of villas. In early Christian art we see a very different approach to the human figure, Stylized bodies of Christian figures like the Virgin Mary are composed in a mosaic, through stones; frontal, symmetrical figures sitting a background of gold–a spiritual representation. In the Renaissance period we do see concerns of representing the body in the here and now. Bodies are rendered employing more natural proportions–there is an interest in naturalism, the realism of the body. It is in the 20th century, with the dismantling of artistic traditions that some artists do not recreate the illusion of reality of the figure. Picasso, for example, abandons linear perspective to depict depth and portrays people on flat canvases from several angles at once. Even the body itself becomes the art work by artists who engage in performance. Feminist artists notably use their own bodies as mediums. The artist’s actions becomes the works of art themselves. Artist Janine Antoni in her performative work “Loving Care”1993. dipped her head in a bucket of hair color, (named in the title for a brand of hair-care products) and proceeded to mop the floor with it, using hair as a paintbrush.

As described through this very brief history of the figure, portrayals of the body are sometimes representational but they are not always portrayed as it “actually looks,” and it may even be altered so much that it does not resemble a real human body at all. The reality of the body can be distorted to suggest great beauty, or to emphasize such qualities as power, status, wisdom, even godlike perfection. Personal and cultural preferences often determine the way an artist chooses to portray a body.

For Peter, his approach to representing the human figure is a personal one. His subjects are people he knows intimately, family, his wife, and of course he is his own subject.

Let’s journey through the landscape of Peter’s self-portrait, his body fully nude. Peter, a middle-aged man, stands in front of a white cushioned armchair, on the wall are tacked up white sheets, and a partial view of a cabinet, leaning against it is a wood shelf or board covered in a white , fringed cloth or fabric. What absorbs my attention is both the nakedness of his body and his gaze. He looks directly at the viewer, but there is no joy or spark in his eyes. His pressed lips are turned downward, his eyes are slightly sunken, atop his chiseled cheekbones are thick graying sideburns. One arm is posed directly by his side, the opposite arm, the left one crosses over his chest, his left hand is tightly clasped around his right arm–the arm becomes like a shield, covering or protecting his openly naked body. It is a bit off-putting to the viewer. He is both vulnerable in his nakedness, yet there is an intensity in the way he holds himself up. What is recorded in this representation of self is a forest of dark hair that covers his body–It is intense–there is a meticulous fervor in the patterns of hair, the pools of hair across his chest, a river of hair flows down his legs. Peter shared with me he is not comfortable with the hairiness of his body, noting the stares he received from bathers at his visits to the beach. In this self-portrait we see and experience the declaration that this is my body, in all its nudity and a sense of not feeling completely comfortable in his own skin, in his vulnerability to expose himself–hence that protective arm crossing over his chest. We see Peter and his body unfiltered.

One painter that creates unfiltered nude bodies who has also influenced and informed Peter and his work is the late Alice Neel. From the writer Ann Binlot: “Neel gravitated in her paintings of the figure to all walks of life– she painted the human form with all of its attributes, its imperfections, and of course–its beauty.” In her honest portrayal of herself, Neel’s “Self Portrait” (1980–she died in 1984) the artist is seated in 3/4 profile on a striped chair. She is nude. She leans slightly forward with a paintbrush and rag in hand. She actively looks back at the viewer “her face flushed..unself-conscious of her nudity and aging body.” We see in her eighty-year-old sagging body, her realness, her imperfections, her vulnerability. Her painting is more loftier, with lighter, more curvaceous lines than the solidness we see in Peter’s form. In both self-portraits, however, what we see unapologetically are glimpse’s of the sitter’s life’s struggles.

Let’s turn towards Peter’s attention of the figure through a painting of his wife. I think you will agree, what is revealed is Peter’s feelings and intimate love for not just the human female body, but for his wife’s body. In the painting Peter portrays his wife from head to the top of her thighs, fully nude leaning against a white table. In the background are white curtains, straight and taut. We see her face in profile; she looks downward, her eyes are closed. One arm is behind her back–the placement of her arms, one hidden behind her back, the other bracing the table draws more of our attention to her body, the curves of her fit figure. The details is in the symmetry of body, round breasts, concave of her belly, sturdy upper thighs. The paint is layered, brushwork thick, he uses a restricted palette of hues–there is no dominant color; he creates contours of the face, bone structure–there is a feeling of flesh. Though the contours are somewhat smooth, there is a sculptural feel to the body, it is almost like a relief. The very surface of the skin we see a splay of freckles at the base of her neck, the body is a vast landscape and an intimate view of pores and stretch marks.

The title of this painting is H. Modigliani–what the title reveals is part of the inspiration behind the painting of Peter’s wife. Modigliani, an early 20th century painter, in the work titled Female Nude he composes a sensuous pose of his sitter, her head tilted to one side, eyes closed. Her body is elongated, it is highly expressive. “In the painting he applies the paint with short stabbing action, manipulating it whilst still wet so the marks of his stiff brush are clearly visible, as are the deeply scratched lines made with the end of his brush to accentuate the model’s hair.” Painted in 1916, the avant-garde artist known for painting furiously, composition of his singular figures are “complex in its range of sources. It adopts the pose of the classical female nude, dreamy and serene in her pose. This contradicts with the ways the artist expressed the body in a rough manner, almost crudely, which was counter to his contemporary artistic standards in the 20th century Europe. Unlike the classical female, Modigliani shows us his love for non-Western art, African and Oceanic in the elongated body and face of his sitter. The painting is described as a clash of cultures. He uses paint that sheds artistic traditions into something more raw and expressive. In comparison to Peter’s wife, she is posed in the same manner as Modigliani’s nude, though Peter holds onto a figure rendered in naturalism, the surface of her skin expresses the nature of her body vs. Modigliani’s thick hue of flesh tones.

For contemporary artists like Peter, there is a direct connection between their work and the works of art they experience. Works by the masters like Modigliani, Neel are channels of inspiration for Peter, a springboard that informs and shapes his vision of his deep love for the body, for humans. Join me now in a conversation with Peter that explores his experiences of the visible world through the masters and the ways they carry over into his creative process.