Experience the ways women artists employ “allegory” and portraiture to demand their place in art history.

Featured Image: Yayoi Kusama, “Self Portrait (TWAY),” 2010

Resources for this podcast episode include Tate Museum, scholarly writings by Robert Hughes and Marilyn Stokstaad and the writings of Amanda Scherker from Artsy magazine. Special thanks to New Britain Museum of American Art.

Script: Episode 120: Women Artists: Allegory in Self Portrait: In my writing space I have a good size collection of art books including a section centered on Women artists organized on a couple of bookshelves. Survey books on women artists in Western art, notable writings by feminist scholars like Linda Nochlin, catalogs from museum collections or feminist exhibitions like Brooklyn Museum’s Global Feminism. Perusing these catalogs and texts is my go to as I think about a woman artist I want to celebrate on the podcast. Flipping through the catalog women artists in the collection at the New Britain Museum of American Art or NBMAA, in New Britain, Connecticut, I came upon a small painting, “Morning, Noon and Night,” by the early 19th century artist Jane Stuart. This painting has some personal significance that I want to share with all of you. I spent a semester as an intern at NBMAA twice, for both my undergraduate and graduate studies, I was a docent which led me into working in Education and later in Development in my more than 10 year tenure at the museum. This painting is one of the first works that led me on this beautiful and compelling path of my deep engagement with women artists. As a young woman, married and with two young children, I was captured by Stuart’s depictions of women, its composition and the narrative behind the work. Let’s dive in.

Jane Stuart’s small oil on wood panel, dated ca 1830-1860, “Morning, Noon and Night” is composed of three women on an oval-shaped panel. The background is the sky with a range of clouds from billowing to roars of dark. The center figure, she is petite wears contemporary, elegant, gold, layered dress; her delicate hands are crossed on her lap. Ringlets of brown curls frame her face. To her right the face of a woman peeks out from over her shoulder. Her arms and hands circle and clasp around the center figure’s arms. Her golden hair is tousled with wispy curls. The third young woman is composed slightly behind the left side of the center figure. Her face is in profile, eyes lowered, revealing thick dark eyelashes that march through her black hair. Her daintily featured face atop her folded hands rests on the shoulder of the middle woman, exposing her partially bare shoulder. Collectively the women’s facial features are expressed doll-like; winsome eyes, turned-up nose, slightly pouty mouths.

From the catalog: “The three beautiful young women represent the times of day, their graceful interlocking poses symbolically uniting them as one perfect entity. Stuart represented the passage of time and the sun’s travels through the sky with the girls’ large, winsome eyes: Morning’s not quite fully open as the sun rises at dawn. Noon’s gazing fully outward as the sun is directly overhead, and Night’s closed as the sun fades from view.”

The painting weaves a narrative of Stuart’s experience as a woman and as a woman of her time. Jane was the daughter of the notable American portrait painter Gilbert Stuart, recognized for his lifelike representations. He brought his stylistic signature, an elegant and suave version of the painterly English portrait: no hard outlines or abrupt transitions, a silvery softness of tone-he created with brushstrokes that rarely blend the colors giving his portraits a “completed quality” He is known for his portraits of President George Washington, including one of wife, Martha Washington. (American Visions–Robert Hughes) His daughter Jane was the youngest of Gilbert’s and his wife’s Charlotte’s twelve children.

From the Gilbert Stuart Museum: “While Jane did not benefit from formal instruction from her father, he refused “to teach her,” she was keen at listening to and observing her father’s instruction to other artists. She helped in Stuart’s studio and he fondly nicknamed her “Boy.” Jane was largely self taught and considered a prodigy even after her father’s death–she ground paints, filled in backgrounds and finished the secondary areas of Stuart’s paintings. She also painted her own works like “Morning Noon and Night.”

“Morning, Noon and Night” personify “her belief in herself as a creative being, not a victim of gender.” This is significant because historically “Western art is replete with images of women and their life experiences created from a male perspective.” As in most of my shows, I try to engage you in mini-art history lessons—Stuart’s painting is allegorical in concept.

Let’s take a closer look at allegory in art as a device used by women to express their assertions about gender–broadly allegory, the term comes from the Latin word allegoria meaning veiled language, is defined as “when the subject of the artwork, or the various elements that form the composition is used to symbolize a deeper moral or spiritual meaning such as life, death, love, virtue, justice,. (Tate Museum) for example, religious symbols in a painting are often portrayed as a dove, or ray of light. An allegory is like a hidden meaning, waiting to be discovered by the viewer.

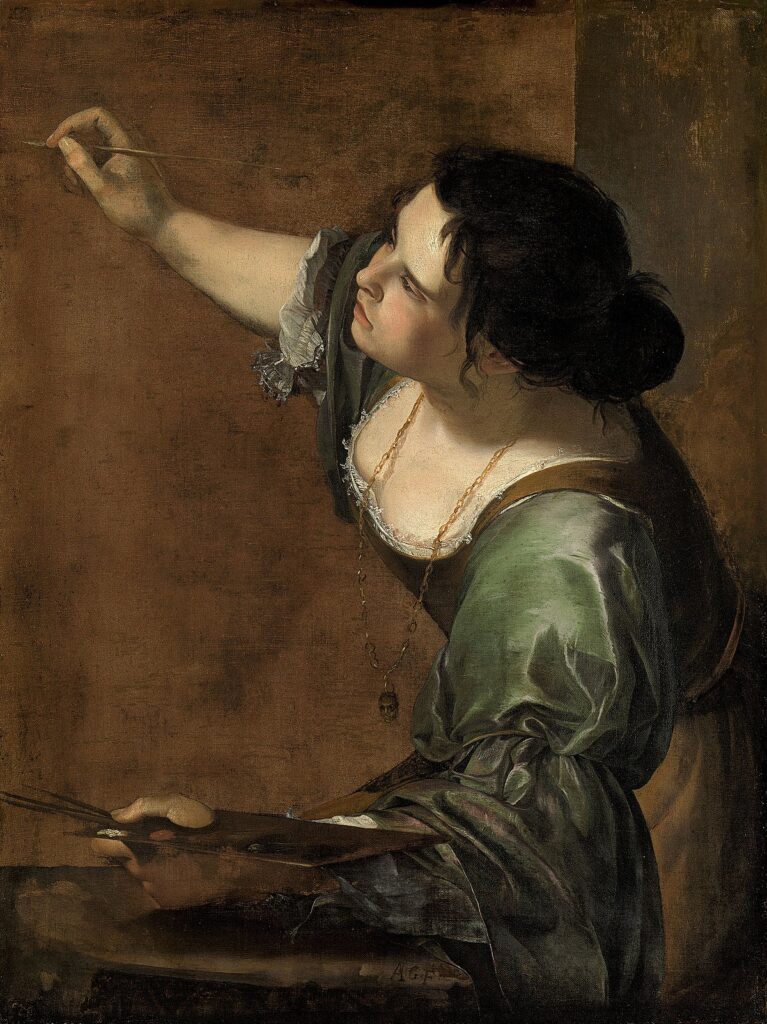

The Baroque–17th century Italy, painter Artemisia Gentileschi used allegory to make “an audacious claim upon the core of artistic tradition; to create an entirely new image of self. In the work “Self Portrait as the Allegory of Painting,” Artemisia depicts herself in the act of painting. She composes herself by depicting attributes of female personification. The work is both a self portrait but also an allegory inspired by the iconography of Cesare Ripa. “In his book Iconologia, a handbook for artists, Ripa gave instructions for the best ways to represent virtues and other abstract concepts in human form through symbolic imagery he compiled. The art of painting Ripa said should be shown as “a beautiful woman with full black hair disheveled and twisted in various ways with arched eyebrows that show imaginative thought, the mouth covered with a cloth tied behind her ears, with a chain of gold at her throat which hangs a mask and has written in front imitation. She holds in her hand a brush and in the other a palette with clothes of evanescently covered drapery.”

Aside from the cloth covering her mouth, Artemisia’s “Self Portrait as the Allegory of Painting,” employs the same symbols into her self portrait. It was an incredibly bold work for its time. Let’s look closely at the elements and the symbols of allegory she transposes from Ripa’s text onto the canvas. We see Artemisia in the act of painting. She is turned away from us focused on a canvas in the distance, beyond the frame of her self-portrait. Diagonal lines, foreshortening techniques–takes the viewer into the painting on both physical and emotional levels. She holds in her hand a brush and in the other the palette–what is notable is she is handling the artist’s tools directly, while in many typical allegorical pictures from the time, they were placed nearby the figure, but not in use–we see Artemisia in the act of painting. Artemisia wears a pendant mask on a gold chain, showing the artist’s capability for imitation of what she sees in life. Her unruly, dark hair depicts “the divine frenzy of the artistic temperament”, or shows the artistic conveyance of depicting work with emotion and inspiration. Her green dress, evanescently covered drapery, follows Ripa’s suggestion that the Allegory of Art is to be depicted in green.

The part that Gentileschi leaves out is a piece of cloth binding the mouth of the allegory, meant to symbolize the non-verbal means of expression that the painter is limited to. One can conclude that this could be Gentileschi’s “mark of refusing to be “kept quiet” or “stay in her place” as a woman at the time, but instead to be bold and proud- neither qualities which were particularly promoted in women at the time. In Artemisia’s radically simplified picture, by contrast with every other example here discussed, the artist emerges forcefully as the living embodiment of the allegory.

Gentileschi took an incredibly egotistical stand- to say that she was not only a female painter at a time when women were not even admitted into the artistic academies- but that as a female painter, she is the very embodiment of painting itself. Her posturing in the piece, with her raised chin, and the dynamics of showing herself deeply focused on the act of painting, also convey a sense of pride- and in addition to that, underscore the idea that she is an artist at work, showing herself in the pursuit of the noble goal of fulfillment, of personal achievement and happiness through her own means.

Contemporary female artists also use self-portrait and allegory to demand their place in art history. In Lois Mailou Jones Self Portrait (1940), we see Mailou Jones the working artist by her canvas brandishing 4 paint brushes. She looks directly at the viewer “proudly declaring her presence as a black female artist. In the background Mailou Jones depicts two African sculptures behind her, as “if declaring her debt to the traditions of those artists, those black artists, who came before her. Through her visual vocabulary, we experience her black identity and the lineage of her African roots.

In Stuart, Gentileschi, Mailou-Jones the human figure is front and center, rendered through naturalism. Abstraction brings in another layer to embedded symbols within female portraiture. One emblematic example is by the painter Yoyoi Kusama, Self Portrait from 2010 is composed completely of polka dots. The image is a frontal view of her face, hair is black with purple streaks, lips pure red are pressed together–she wears a turquoise turtleneck.

Kusama explained that “dots are symbols of the world, the cosmos. The Earth is a dot, the moon, the sun, the stars are all made up of dots. You and me, we are dots.” In Self Portrait (TWAY) from 2010, she literalized that sentiment. The painting, with its complementary yellow and purple patterns of dots, seems to indicate that the painter sees herself at one with the world around her.” I feel when I hike and I am encompassed by groves of trees, the outstretched limbs above my head. I am one with nature–Kusama expands this sentiment into the cosmos. And she expresses it through the shape of a dot.

Across over centuries, from Gentileschi to Stuart to Mailou-Jones and Kusama–we experience the tenacity from its visual composers. I am so struck by the way the women use symbolism to express their boldness. They take from the visual world, artistic traditions defined by men and then re-envision it to fit their own narrative. They inspire me to create my own allegorical self portrait, Over the summer, I am making a list of objects associated with my life, what they symbolize for me. I plan to combine drawing and photography to create a work that embodies those ideas in a self portrait. In a future episode I will share with you the finished work. Care to join me to create an allegorical self portrait? Email me at bernadine@beyondthepaint.net