I invite you to join me on an audio tour of painting and photographs; representations of the female figure through the female perspective and feminine experience by four American women artists; Polly Thayer, Lee Krasner, Carrie Mae Weems and Martine Gutierrez. We will experience them through the collection of the New Britain Museum of American Art and consider the ways women shape collections and the canon of Western art.

The images highlighted in this episode are featured below. You can explore these works through the New Britain Museum of American Art, EMuseum.

Script: Episode 123: View from a Collection: Women, The Figure and NBMAA

In this episode we will look at how the feminist lens can change the way we look at the female body in Western art, specifically within the works by American women. My interest for this topic is to share an aspect of my work as an educator in central Connecticut. I design and lead adult tours highlighting women artists and their contributions to the visual arts in museum collections. Currently I am contemplating works currently on view from the collection at the New Britain Museum of American Art in New Britain, Connecticut. And I am inviting you to come along with me! An audio journey through the museum’s gallery spaces to engage you with the female figure from the female perspective and feminine experience; to contemplate women artists you may not know or be aware of, and to further explore these works on your own. I will add links to the show notes.

Traditionally representations of the female figure exclude the female viewpoint. This is a pervasive theme in my podcast series. This audio tour will highlight the ways women artists “approach the nude or female figure with their own agencies and agendas—an exploration of female experience and subjectivity. I present four works from the tour, created in the 20thor 21st centuries; these are American woman producing art in the United States— this is the time period women artists thrive in their production of the figure in objects of art. Throughout the 19th century women artists, most women, were excluded from life drawing and anatomy classes essential in attaining the ability to render the human form—this was justified by the belief it would be indecent and endanger innate female modesty. This changed towards the end of the 19th century because of the demands of women—American art schools offered life drawing with nude models to women.

Before we dive in or take our first steps into the gallery, allow me to share with you about the museum. Founded in 1903, New Britain Museum of American Art is the first museum in the country dedicated to American art—its collection represents the major artists and movements of American art. Women’s contributions have shaped the museum, challenging underrepresentation and celebrating diversity.

I want to credit a wonderful resource for this tour of women: catalog Women Artists @NewBritainMuseum for their scholarly essays and perspectives.

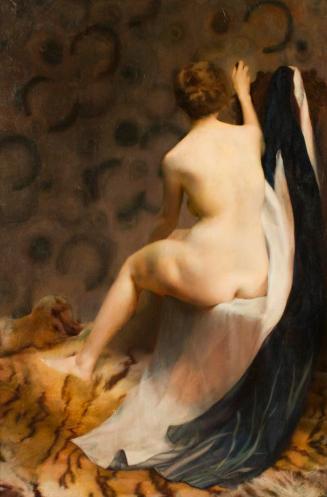

Let’s dive in and look at the female nude subject that follows a tradition in Western art that dates to the Renaissance, early 20th century painter, from Boston, Polly Thayer, her oil on canvas, from 1928 “Circles.”

On a large canvas, we see the back of a fully nude woman sitting on flowing, silken robe or drapery, she is alone and her back faces us–, a tiger’s rug is beneath her feet. Her body curves, from her dainty shoulders, the eye is led to her small waist that opens to her full hips, her left leg is fully exposed, we see a dimple in her upper thigh. Her auburn hair is pulled up in a loose fitting bun. What is striking about the painting is the background—it is textured with overlapping circles of purple and lilac. “Their roundness is echoed in the roundness of the figure’s body, the shape of the tiger’s head, and the sweeping position of her robe, all guiding the viewer’s eye from one rounded form to another.” Representations of the female figure, including the nude figure have been the prerogative of Western male artists since the Renaissance. What follows is the growing consciousness that “the female nude as created and defined by male artists typically becomes an object for the spectator’s gaze; an implied relationship is formed in which the female nude has no individuality or power but is instead a passive object of sexual desire for the presumed heterosexual viewer.” Thayer demonstrates that she was a highly accomplished proponent of academic realism, yet asserts her artistic individuality by creating a “female nude that is uniquely elegant and refined yet physically imposing and intensely sensuous.” Within the traditions of the academic, Thayer, the woman, creates a sense of eroticism by juxtaposing textures and designs.”

I think that the choice to have the woman turn away from the viewer, the choice of not seeing her identity or meeting her gaze holds our focus, our attention not just on the figure,but the surrounding patterns and textures, from the circles, to the lush tiger rug to the white and midnight blue drapery—all these lead our eye to the curves and sensuality of the woman’s body, a body that in its relatable ordinariness is extraordinary.

Let’s turn our attention to a nude figure, smaller work by artist Lee Krasner, charcoal on paper, was composed about 10 after the Thayer painting, “Nude Study, 1939.” It is purely an abstracted view of the female nude, rendered in the Cubist mode—Krasner presents multiple viewpoints of its subject, not a single, linear viewpoint like we see in traditional paintings, like the Thayer painting. This is accomplished by creating more angles and planes, Cubists works often seem to be made up of geometric shapes. For Krasner, “The nude is the vehicle for the investigation of abstraction and the declaration of artistic independence from ways of representing three dimensional forms in use since the Renaissance. Instead of embracing traditions, she dismantles traditions. Her female nude is composed of “Arcs and circular lines suggest the female nude’s contours alternate rhythmically with rectilinear lines and shapes that imply the fluctuating space around her. “ There is a sense of movement in her figures; Krasner did these studies when she was a student of Hans Hoffman, the most influential teacher of his day in New York. She worked from live models, transforming the three dimensional into a series of planes that “evolve from the constant erasing and reworking of the lines. Thus the work is more about the process of creation than about the product itself.” In Krasner we experience not just the breadth and beauty or the sensuality of the body as we did with Thayer, but about the creative process, it becomes paramount over the “product itself,” we experience within those geometric shapes the “creative mind of the artist at work.”

Side Note: Lee Krasner was the wife of Abstract Expressionist pioneer Jackson Pollock who really came into her own as an artist after Pollock’s death. In 1956 she moved into the barn studio at their home near East Hampton, Long Island, increased the scale and intensity of her work, and tapped the more personal content that had been repressed and dormant during her marriage.During the next quarter century, Krasner drove dynamically through a number of style shifts, achieving at her peak a powerful, dramatic, and at times disturbing imagery based on the forces of nature. Krasner’s cubist background had given her a strong sense of how to manage her pictorial field as a whole. She should not be dismissed as a minor talent, working under the shadow of a great artist. Rather, her early work tells us that she was a deeply committed artist struggling with various styles and concepts long before she met Pollock.

We looked at Thayer and the figure rendered through artistic traditions, Krasner’s abstraction of the female, nude figure—let’s consider the black female figure through artist and photographer Carrie Mae Weems.

“Not Manet’s Type” 2010 is asequential series of five framed individual photographs accompanied by text or brief inscriptions, Weems takes the role of a muse in each of the image’s five nude self-portraits. Each of the statements may be read as a feminist response to the way in which male artists have used or objectified women’s bodies and a commentary on the presence of black women or lack thereof in the history of modern art. The canon of art is her starting point. Weems uses the medium, photography, as an expression of her activism—she looks at history as a way of better understanding the present. She says, “Photography can be used as a powerful weapon toward instituting political and cultural change. I for one will continue to work toward this end.”

The scene or backdrop for each photograph is a bedroom, in the center of the image is a brass bed against a window—it is reflected in a round mirror atop a dresser. Weems inserts herself, her body in each image. Each photograph references male artists, giants of Western art and patriarchal view of the female body. In one image Weems stands in a classic contrapposto pose at the foot of an unmade bed. She “deliberates how to prepare for critical study. The inscription below the photograph says: “Standing on Shakey Ground/I posed myself for critical study/but was no longer certain/of the questions to ask”Weems serves as both muse and creator, she imparts a sly duality to her challenge of the examination of woman as the subject of an artist’s gaze, and her role as an unrepresented creative voice—the black female

Weems continues to guide the viewer through her rumination by incorporating mentions of canonical figures of art history in her texts. Below the image of Weems, again standing with her back to the viewer, the text reads: “IT WAS CLEAR I WAS NOT MANET’S TYPE / PICASSO – WHO HAD A WAY WITH WOMEN – / ONLY USED ME & DUCHAMP NEVER / EVEN CONSIDERED ME”. By actively positioning herself among such recognizable male artists, male giants in the art world, she both offers a familiar entry point with which viewers can engage while also laying the groundwork for exploring inherent power disparities in the art world. She closes the series with a self-portrait, referencing the female artist Frida Kahlo; she is on her back, relaxing across the room’s bed, and she looks up at the ceiling. The text reads “I TOOK A TIP FROM FRIDA / WHO FROM HER BED PAINTED INCESSANTLY – BEAUTIFULLY / WHILE DIEGO SCALED THE SCAFFOLDS / TO THE TOP OF THE WORLD”.

This series, though engaging and beautifully, cinematically rendered, to the unfamiliar viewer, demands further inquiry—to understand the references and the artists she engages us to. For example Frida Kahlo’s husband is the muralist Diego Rivera; Manet, the 19th century painter dismantled the traditions of the female nude in his painting “Olympia,” creating female imagery that optimized Caucasian skin and essential erases the Black figure. Weems says, “I cannot rely on these artists. As much as I love them, I revere them, I’m also very, very disappointed in their engagement of the historical body of the Black self, of the Black body, of the Black imagination.” This series “recalibrates and challenges our assumptions about Black women in art.” Weems is quoted, “I think the idea of unrequited love is really a very intense part of the work. I am always questioning what’s been left in and what’s been left out. And so then, how to reframe, how to reposition, and how to insert, for the first time, a body that has not often been there, or to pull forward a body that rests in the background. This historical body has not been for the most part, the subject of these great painters. It is not a part of their imagination, it is not a part of their fantasy. But of course art has a great deal to do with imagining the unimaginable.

The final image, another photograph is a self-portrait of artist Martine Gutierrez, she is of Guatemalan and American descent. She documents “her exploration of heritage, gender fluidity, trans-identity and LGBTZ and Latinx beauty. The photograph, framed and installed in the gallery space of the museum’s contemporary collection, is part of Gutierrez’s production of 124 page glossy magazine with fictional advertising and high-fashion spreads titled Indigenous Woman, throughout its pages the artists continually reinvents herself. Through the style and construct of the glossy magazine, Gutierrez subverts conventional ideals of beauty to reveal deeply-entrenched attitudes of sexism, racism and transphobia in society.

The print, “Neo-Indeo, Cakchiquel Calor, pg. 34 from Indigenous Woman” we see a singular woman in a white background including the ground beneath her feet—Guiterrez models Guatemalan textiles sourced from her family’s collection, the long, straight skirt is bright red with horizontal stripes of yellow and pink, there is a spray of flowers in the front. Her shirt is yellow and ornamented with vines of pinks and purples. She balances a clay bowl atop her head covered in flowing head piece. Her fashion of traditional Mayan trajes de Guatemala, illustrates a “contemporary living history, not one that is just buried.” The fashion industry often appropriates indigenous culture through its design but rarely credits the source, and some designers even claim credit. “Neo Indeo” functions as a commentary on the invisibility of living indigenous craftsmanship and the appropriation that designers often perpetrate. It’s reframing indigenous identity beyond the typical tropes of nostalgia, poverty, and antiquity. “This is how your abuelita (grandmother) might dress, but this is also how her granddaughter is going to dress,” Gutierrez explained.

The latter two artists, Carrie Mae Weems and Martine Guitteriez are contemporary artists—they boldly drop a gauntlet on any semblance of resistance for inclusivity in the art world. For me as the viewer, the spectator, they reveal alongside women artists like Thayer and Krasner, deeply entrenched attitudes of “sexism, racism, our phobia or bias towards the LGBTQ community. Collectively these four women, through four works of art spanning over 100 years call attention to new ways of seeing and experiencing the female figure in art.

Thank you for listening. The four works and artists highlighted in this episode are in the show notes. I would love to hear the ways these women and works resonate with you. Email me at Bernadine@beyondthepaint.net–I will happily share your thoughts, your insights on a future podcast. Thank you!