Explore with me printmaking through the lens of three 20th century black, women artists; Elizabeth Catlett, Faith Ringgold, Kara Walker.

.

This episode also contemplates the historical importance and the embedded narrative of the female experience of European and American women printmakers in the story of Western Art.

Featured Image: Elizabeth Catlett: “There is a Woman in Every Color,” 1975, color linoleum cut, screen print and woodcut.

Resources for this episode include the following:

Texts: Brodsky, Judith. “Some Notes on Women Printmakers.” Art Journal, Summer, 1976, Vol. 35, No. 4, pp. 374-377. Chadwick, Whitney. “Women, Art, and Society.” New York: Thames and Hudson Publishers, 2007. Farrington, Lisa E. “Creating Their Own Image: The History of African-American Women Artists.” Oxford University Press, 2005. Lewis, Samella. “African American Art and Artists.” University of California, 2003.

Museum Resources: British Museum: www.britishmuseum.org; Louvre Museum: www.louvre.fr/en/; Mary Ryan Gallery: https://maryryangallery.com/; National Museum of Women in the Arts: www.nmwa.org; New Britain Museum of American Art: www.nbmaa.org

Script:

Welcome to Episode 150: This episode is inspired by a recent talk I led at the New Britain Museum of American Art for their Museum Masters series, mini-lessons in American art history. I explore printmaking through the lens of black, women artists. We will consider the black female experience, through the works and practice of three, 20th century American women artists, Elizabeth Catlett, Faith Ringgold, Kara Walker

Before we dive into these American female printmakers let’s consider some of the history of European and American women printmakers, and their importance in the story of Western art, but also to consider the feminine sensibility, the narrative of the female experience that is embedded in these works. The way I arranged this is I highlighted pioneer women, master printmakers from the 16th century to the present. We will look at women from two artistic centers Italy and Northern Europe until we get to the 19th century which will include the United States and other artistic centers in Europe like Paris and Berlin.

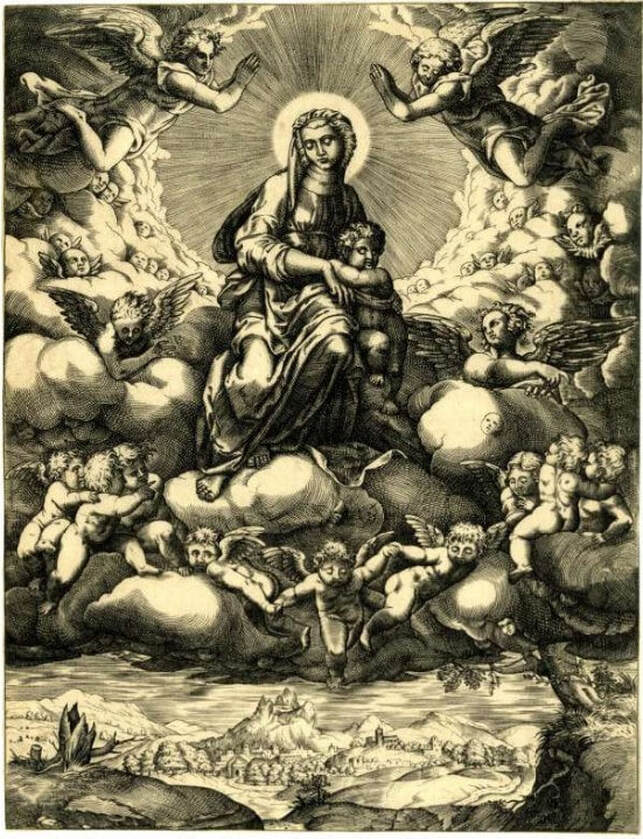

An early female printmaker is Diana Scultori from Italy, an engraver from the mid-16th century, who engraved some 62 prints, mainly of religious and mythological subjects. Part of the reason we know about Scultori’s work at all is that she signed her prints, works like “The Virgin Mary and Child accompanied by many angels and seated on a bank of clouds.” The central figures are Mary, a halo radiates brightly in long thin streams of light around her head, and her baby son Jesus clutching at his mother’s waist, anchored below billowing clouds are cherub shaped angels and in the far distance we see a landscape of mountains and trees, the details are exquisite. The imagery in Scultori’s printmaking is representational—iconic figures, objects in nature, heavenly angels they are part of the Christian narrative.

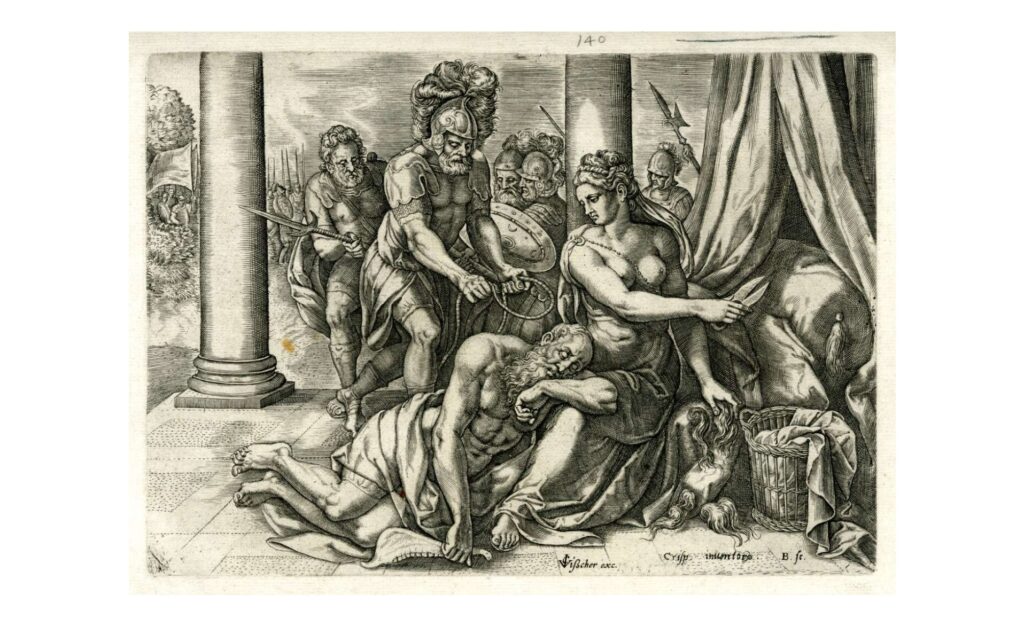

Barbara van den Broeck (Holland, b. 1560) She worked in her father, printmaker Crispin van den Broeck workshop. From the Old Testament Samson and Delilah: Samson is asleep in Delilah’s lap at the center of the image. She is cutting his hair, an attribute to his physical strength with a pair of scissors, as soldiers with feathered helmets approach Samson with a cord from behind. His affection for Delilah led Samson to blindness, imprisonment and powerlessness. Both Van den Broeck and Scultori render the textures of the drapery, the landscape so beautifully, the figures are elegantly stylized.

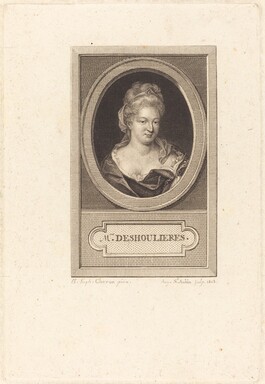

17th century, from Italy Elisabetta Siriani, daughter of painter Giovanni Siriani, she ran the family’s workshop. When her father became incapacitated by gout, she supported her parents, three siblings, and herself entirely through her art. She was one of the few women or men to work from their own designs. In the print, “Holy Family with St. Elizabeth and St. John the Baptist, etching on paper (1650-1660)—10 ½ x 8 ½ the artist portrays the figures in a domestic setting, not in the Heavens. The Virgin Mary nurses Jesus, who rests across her lap. Saint John squirms at her feet, reaching for the object that Mary dangles in front of him. Saint Elizabeth sits at the right, and Saint Joseph, carpentry tools in hand, occupies the background. Presenting Jesus and his cousin John the Baptist as ordinary, playful children emphasizes Sirani’s familiar and affectionate approach. She illustrates complex fabric folds. One of the first women admitted to the French Academy, Elisabeth Sophie Cheron. Daughter of the miniaturist Henri Cheron, Sophie was a gifted painter, engraver, poet, musician, academic and translator of the Psalms. Her engravings include portraits of famous figures like Antoinette du Ligier de la Garde Deshoulieres,1803– A major poet during the reign of Louis XIV in France.

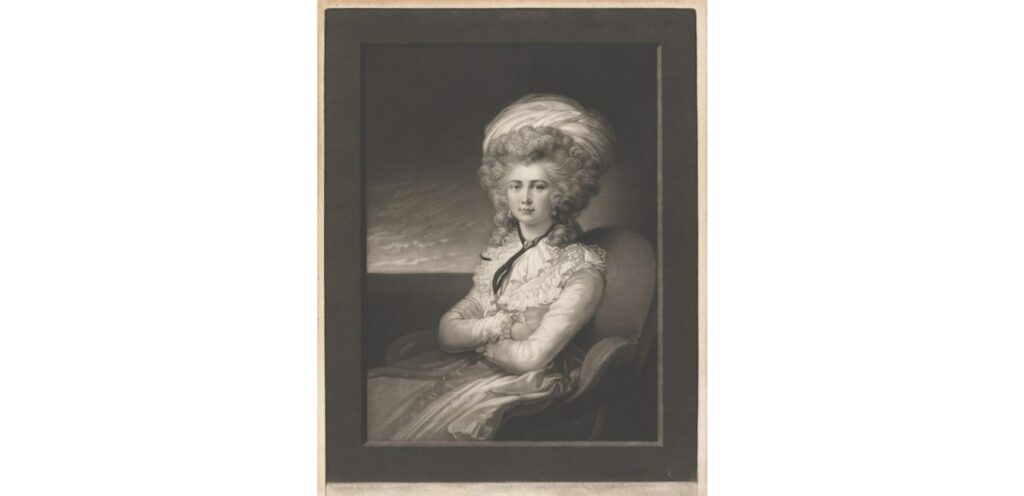

18th century: In addition to the women who were engraving professionally in this period, women in the aristocracy took up printmaking as a fashionable hobby. Maria Cosway: born in Italy to English parents, wife of miniaturist Richard Cosway, she was part of Thomas Jefferson’s intimate circle of friends during his time in France—she had immense knowledge of art and some of her works include political prints during the French Revolution. She was also known for her brilliant allegorical works, “Repelling the Spirit of Melancholy” “The three holy women lament over the dead body of Christ.” Mezzoprint, both c. 1800 (Mary, Mary Magdalene, Salome)

19th century: Mary Cassatt: American born, she traveled to France for her artistic training and remained there most of her life and career. Signature subjects were portraits of women, children and portrayals of mothers and children caught in everyday moments—what surfaces are insightful evocations of women’s inner lives. “Antoine Holding her Child” medium is dry point, 8 1/4 x 5 1/8 in, 1908 Mary Nimmo Moran, Thomas Moran’s wife—etching of “Figure in the Woods” intaglio, 12×8 ¼(1888); –we see the majesty of nature through an intimate lens. Moran’s “intimate scenes of people walking in the landscape are very pleasing. They recall journeys through the woods enjoyed by the artist and her female companions. Giant trees overwhelm and overshadow the traveler; figure is dwarfed by the trees.”

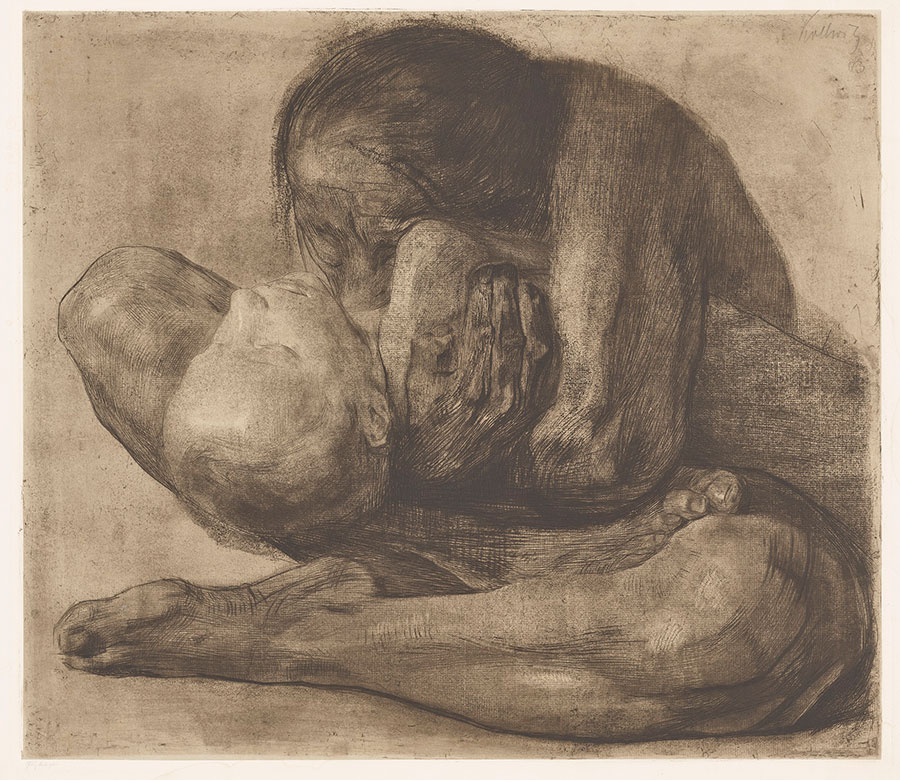

20th century: Kathe Kollwitz: German printmaker and sculptor replace the archetypal imagery of female abundance with the realities of female bodies marked by poverty which often prevents women from nourishing their children or enjoying their motherhood. Through expressive mediums of engraving and lithography, Kollwitz turned to themes of social conditions. She was committed to portraying the plights of workers and peasants. Kollwitz had a real affection for working class. From her series “The Weaver’s Rebellion,” Kollwitz expresses an intimate reflection of the artist’s affection for working classes; she forces viewers to confront the vulnerability of working class people struggling to survive. Kollwitz presents women as active participants in this struggle. The Weaver’s Rebellion series begins with the work on the bottom right, “Misery,” (1897, lithograph) a scene showing the death of a child from the deprivations of poverty, a direct reaction to a life cut short by low wages and inhumane conditions. Kollwitz’s iconic work “Mother with Dead Child” (1903, lithograph) has been compared “something like a Pieta”—there is only pain, this composition culminates Kollwitz’s personal experience and observation. Her own son Peter died in World War I. Kollwitz believed art should affect social change—keep that in mind because that belief and value of the purpose of art is prevalent in the works of the black female printmakers we will explore in a moment. You will notice some parallels in the works.

Notable American female artists in the 20th century: Isabel Bishop etching “Noon Hour” 1935 “Showing the Snapshot” 1936 etching—both illustrate Bishop’s observations of working women in the city Bishop was a member of New York’s 14th Street School, moving to Union Square in 1926—here she became enamored with the area and its inhabitant, shop girls, laborers, and derelicts became her models as they traversed the city. In her etchings from 1935 and 36: “Noon Hour” and “Showing the Snapshot,” both illustrate Bishop’s observations of working women in the city, capturing their motions and gestures. Wanda Gag: illustrator of books: lithograph—size approximate 12×10 “Winter Twilight” 1927 and the “Backyard Corner” 1930. Gag’s subjects are charmingly familiar—ordinary things spring to life, “as if drawing itself animates the objects depicted.” There is this palpable intensity and vitality—an expressive interchange between the artist and the world she inhabits. She authored the book Millions of Cats. Louise Nevelson: Non-representational, abstract “Untitled, 7 a.m.” 1967, color lithograph, 36×26 in. Combining two identical prints in reverse vertical position, Nevelson engages her practice of reusing and balancing large rectangular forms and an array of small details—non-figural, non-representational, exploration of form vs. traditional explorations of the figure and the human experience.

Let’s shift to 20th century black female printmakers. Focus of the imagery for this talk is the female figure, the body and the configuration of the black female image without embedded racial and gender stereotypes. Printmaker and Sculptor: Elizabeth Catlett: Born in 1915 in Washington D C, Catlett professed to have inherited her creative aptitude from her father, an accomplished musician and woodcarver who died just a few months before her birth. Staunch support and encouragement from her mother and high school teacher led her to an immersive and resolute life in the visual arts and active interest in politics. In her tenure at Howard University Catlett came into contact with several key players of the Harlem Renaissance who were instrumental in her aesthetic and ideological development. Through these influential teachers, Catlett in her art would enhance the image and enrich the lives of people of color. Catlett said that purpose of her work was “to present black people in their beauty and dignity for us and others to understand and enjoy.” Question to ask–What do images do to enrich the lives of people of color?

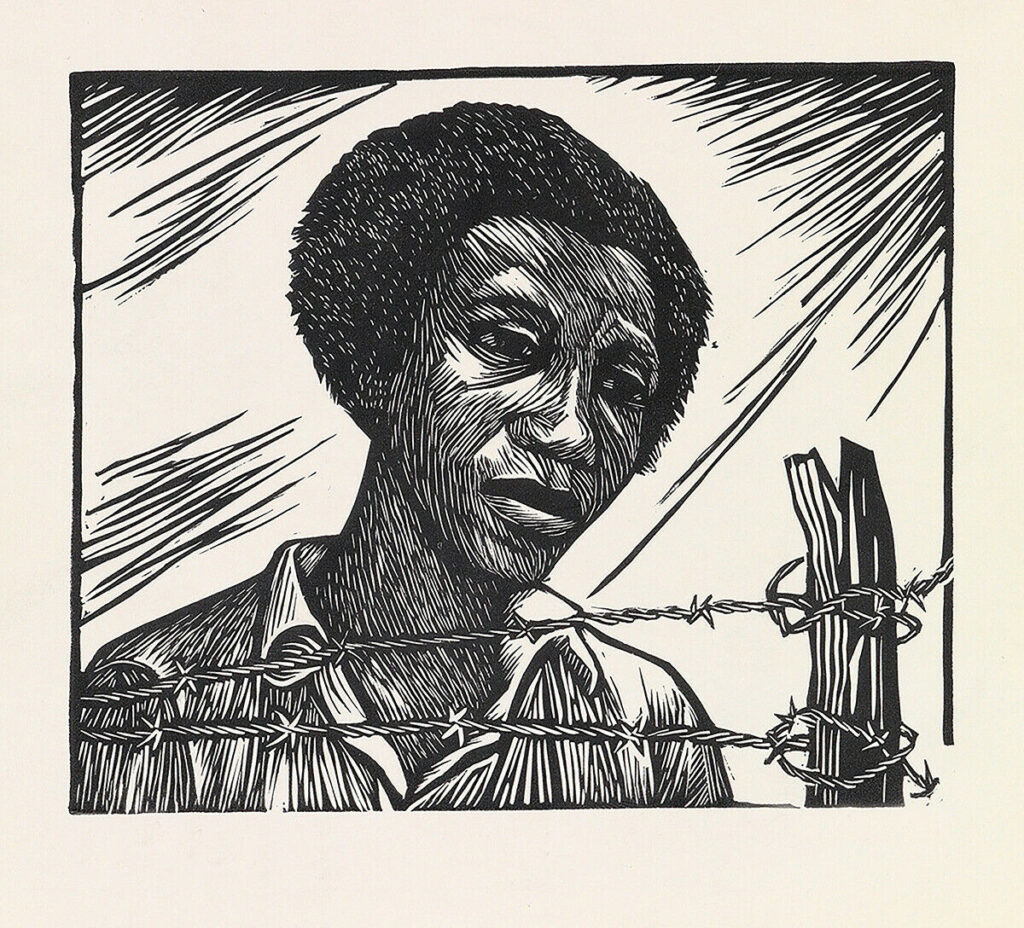

Let’s dive into a few works from a series or cycle of 15 linocut prints with textural hatchings on the subject of black women (1945 and 1946) entitled “The Negro Women” series later renamed “The Black Woman Speaks.” Awarded a Rosenwald fellowship to produce the series, Catlett used the funds to study in Mexico. She became enamored of Mexico where she felt less hampered by racial bigotry. “I feel like a person in Mexico. When I am in the States, I feel very conscious of what my race is.” Catlett permanently settled there, raising three sons.

The titles in the series read like an autobiographical narrative, suggesting Catlett’s commitment to the subject of the black women. They are dedicated to the archetypal peasant woman, as well as to several explicit historic heroines. The series was revolutionary for its time as a narrative of previously unrepresented history, resistance, endurance and hope. It is an epic commemoration of the historic oppression, resistance and survival of African-American women. Visually each print is “close-cropped, starkly chiseled, simultaneously intimate and monumental.

For the anonymous, ordinary women, we engage in the private realities of their lives. #1: “I am the Negro Woman” anonymous, close cropped, detailed-this print alongside the others is intimate, highlights “lived experience as a means of truth telling.” Catlett “rescues the anonymous woman from the margins.” #7: “In Harriet Tubman I Helped Hundreds to Freedom shows black heroic social uplift through radical self-emancipation. In the print In Harriet Tubman I helped hundreds to freedom a group of slaves are walking in a procession grouped behind Harriet Tubman. This group could represent the slaves who imagined themselves as freed people, and then acted with agency to escape through Tubman’s guidance. Though the state did not recognize slaves as freed people, the slaves decided to grant themselves freedom by escaping. #11: “My reward has been bars between me and the rest of the land.” The print celebrates “unknown women” and the invisible labor. Whether it’s in the home, or in the field, or in the factory, the ‘unknown’ black woman frequently wasn’t seen or wasn’t made heroic. For Catlett, the idea was to celebrate the everyday labor of ones who have not been noticed, who go unnoticed throughout their work. #15: “My right is a future of equality with other Americans” close-cropped powerfully modeled woman’s head—note the energetic sense of lines and patterning. Catlett’s monumental figure gazes upward in a pose of hope, strength and achievement. The last print I like to share is from 1975: There is a Woman in Every Color, 1975, color linoleum cut, screenprint, and woodcut, 22×29 “This print experiments with several techniques to capture different representations of Black women. The woman’s dignified face is rendered as both positive and negative, perhaps suggesting a call for racial equality. Catlett’s inclusion of the multicolored women on the right references the color bar that registers color accuracy in printing. Here, it enacts an integration of the margins (or marginalized) that can be read as a metaphor for the artist’s commitments to global civil rights and equality. The colorful women suggest an accessible and intersectional movement of feminism that would call for the liberation of all women.”

Catlett earned the title “foremother of the Black Arts movement.” She would come to share this designation with another 1960s revolutionary, Faith Ringgold. Ringgold has long been involved in the struggle for equality for women, and she feels that her most profound artistic contribution has been in “women’s art.” She said, “My art is for everyone but it is about me (my sisters.” Through her artwork, Ringgold commented on racial issues in the United States, evoking truthful imagery of a Black and white America. The Sunflower Quilting Bee at Arles, 1996, lithograph, 22 in. x 29 3/8 in. Made after the quilt painting of the same name, The Sunflower Quilting Bee at Arles depicts several prominent African American women constructing a sunflower-patterned quilt. Standing among a field of sunflowers, the women who hold the quilt are relatively well known in American history – Madam CJ Walker, Sojourner Truth, Ida B. Wells, Fannie Lou Hamer, Harriet Tubman, Rosa Parks, Mary McLeod Bethune, and Ella Baker. Willia Marie Simone, the fictional ninth figure in the lower left, is included as a young woman who journeys throughout Europe to become an artist. In this lithograph, artist Faith Ringgold celebrates the contributions of Black women to abolition, civil rights, and women’s rights while centering the collective, traditionally female art of quilting. Black women since the nineteenth century have participated in the tradition of quilting, resourcefully creating elaborate and abstract quilt compositions.

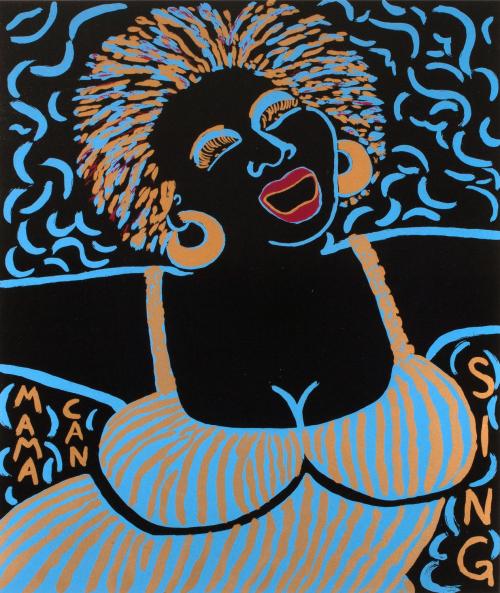

From her “Jazz Stories,” 2004, “Mama Can Sing,” the series expresses the vibrant legacy of jazz. Ringgold explicitly incorporated the soundtrack of her youth into her art. “I’m definitely not a musician of any kind,” she says with a laugh. “But the music was rampant – it was all over the place.” Growing up in the creative and intellectual context of the Harlem Renaissance, Ringgold’s life has been surrounded by jazz musicians, many of whom continue to inspire her practice. The series is characteristically bold, colorful style. In this image of a liberated black female, the voice of the repressed can be heard through the song and vibration of black, blue, and gold. Ringgold addresses her own insecurities towards weight and female self image by presenting an image of a carefree, voluptuous female. “Mama Can Sing” is an image of a woman who is comfortable in her own skin, even if she is “black and blue” on the inside. Ringgold says about the women in works, “My women are actually flying; they are just free, totally.”

One of the youngest and most controversial late 20th century black female artists is the Conceptualist Kara Walker She earned her MFA at RISD, Rhode Island School of Design. What catapulted this avant garde artist is her “stunning and aesthetically seductive” black paper cut outs. The one shown here, “Slavery Slavery”(1997) is a monumental panoramic journey into picturesque southern slavery. Using the traditional craft of cut-paper silhouette portraits (this form of portraiture began in the mid-18th century), Walker mounts large format, lyrical, vintage style illustrations. onto white gallery walls. She depicts slavery, death, interracial violence and biological and sexual depravity acted out by characters from the antebellum era—the American South in the years after the Civil War. The carefully composed and executed hand-cut silhouettes scrutinize structures of power, specifically those based on racial and sexual violence. She draws from racial clichés like the Mammy and portrays white plantation masters, mistresses and children.

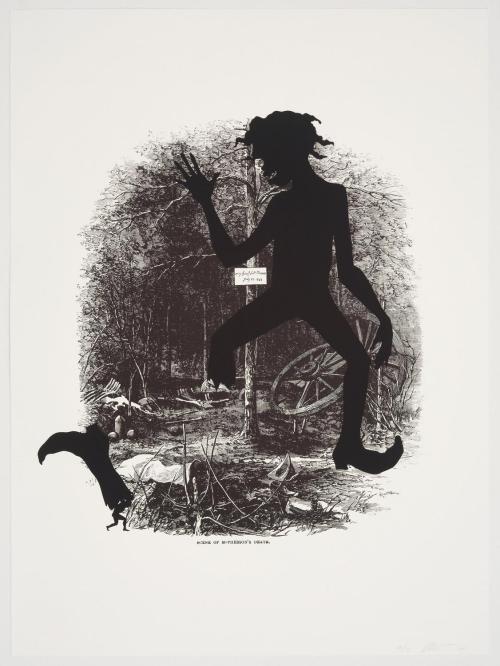

Recently the New Britain Museum acquired Walker’s 2005 print series “Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War (Annotated)”. In 2005, Walker worked in collaboration with the LeRoy Neiman Center for Print Studies, New York, to produce the series, a portfolio of 15 prints that considers experiences of racism toward African Americans that were absent or only alluded to in historical representations of the Civil War. Each print in the portfolio is an enlargement of a woodcut plate from Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War, overlaid with Walker’s silkscreen cutout figures rendered in solid black silhouette. The intent of the originally published prints published in 1866 was “narrating events of the war just as they occurred.” By overlaying silhouette figures upon the scenes, Walker visually disrupts the original images and suffuses them with traumatic scenarios left out of the “official record.” She activates the past in order to address the reality of racial conflict that persists today.

“Exodus of Confederates from Atlanta” An important rail and supply center, Atlanta, Georgia, fell to Union troops on September 2, 1864, after a series of Confederate defeats in and around the city. Many inhabitants, along with Confederate troops, began to evacuate the city before the arrival of Union troops, as depicted in this Harper’s illustration Exodus of Confederates from Atlanta. Walker adds psychological and visual complexity to the scene, through the inclusion of two large silhouettes of an African American women and man—one nested within the other to create an aperture or window into the Harper’s image beneath. The silhouettes draw the viewer’s eye toward the center of the composition, where an African American boy can be seen loading a caravan for civilians who were ordered to evacuate the city, raising questions about the plight of the enslaved residents of Atlanta. “Scene of McPherson’s Death” James Birdseye McPherson was a career United States Army officer who served as a general in the Union Army. During the Battle for Atlanta in 1864, McPherson was shot and killed when he unexpectedly encountered Confederate skirmishers. He became the second-highest-ranking Union officer killed in action during the war. Despite his death, the city of Atlanta was overtaken by Union troops one month later. This Harper’s illustration depicts the aftermath of McPherson’s death. The site is littered with remains of the battle, including cannonballs, wagon wheels, and a horse’s skeleton. Superimposed over this image, Walker’s silhouette of a youth looking in shock at his severed foot captures the mayhem and brutality of the era.

I want to end this talk with a quote by the scholar Lisa Farrington: “Visual art is a form of language. As such it has the palpable power to define and communicate particularized ideas as well as collective cultural codes. Makers of art throughout history have exercised their immanent right to define themselves through art and to fashion a self-definition that reveals them and their respective societies in the best possible light. African American women artists have exercised the same right, but until recently their voices have been hushed by the bellows of outsiders. I think you will agree the elevation of black women artists, their voices are now thunderous and will continue to resonate over time. As Faith Ringgold said, “You should never make something as an artist or even as a writer that is outside of your experience. People will use what is available to them. I am black and I am a woman. There it is.”