Beyond the Paint podcast celebrates the visionary artist Pamela Colman Smith in two parts. Part 1, focuses and highlights aspects of Smith’s artistic life and practice.

.

Part 2-will take a deep dive into Smith’s legacy as illustrator for the Rider-Waite tarot deck, a commission she described as “big job for very little cash.” (launched late April, 2022)

.

Resources for this episode include Yale Art Gallery and the seminal text “Pamela Colman Smith: The Untold Story” by Stephen R. Kaplan with contributions by scholars like Mary K. Greer.

.

Image credits include Mary K. Greer (blogsite) and Kaplan Text

Special thanks to K. Lee Marks @k.leemarks (IG) and the creators Grant Walker and Amy B. Scott of Seeds of Initiation Tarot deck @seeds_of_initiation_tarot (IG) for inspiring this journey into Smith’s evocative and mystical visual imagery.

.

Special shout out to the women who bring awareness and create arenas for contemporary women artists to flourish!

Liezel Strauss: Art Girls Rising: www.artgirlrising.com

Hall Rockefeller: Less than Half Salon: www.lessthanhalf.org

Kelly Groehler: Alice Riot: www.aliceriot.com

Welcome my art enthusiasts to Episode 156: Rider-Waite Tarot Deck Illustrator: Pamela Colman Smith. I am presenting this early 20th century artist, known as Pixie in two parts. Part 1 will focus and highlight aspects of the life and practice of the artist who is behind the visual language of the Rider Waite tarot deck. In Part 2, which will be launched in about a week, we will take an in depth look at the creation of the Rider Waite tarot deck, the history and purpose of the deck as a divination tool, the scholarly mystic and co-creator of the deck Arthur Edward Waite who commissioned Smith to create the card’s illustrations. Smith described the commission as “a big job for very little cash.” Initially I planned to craft one episode exploring Smith’s visionary tarot designs. Veiled with a mysterious faux medieval atmosphere, the imagery for the cards is rich in symbolic detail. But in my research, I was blown away by Smith, as a woman artist and creator—she lived an unconventional life, she was connected with known artists, writers, musicians—I was especially moved by her stand on women artists of her time and the challenges she faced in a world that “tried to muffle women’s artistic voices or at the very least keep them in the rigid confines waiting to be liberated. “

So let’s dive in-Pamela Colman Smith was an illustrator, poet, folklorist, editor, publisher, costume and stage designer (born in 1878, died in 1951 in her “beloved” Cornwall, England of myocardial degeneration) “drew inspiration from her own life, beliefs, interests and friends.” And this is where my deep enthusiasm aligns in regards to Smith’s works and practice. If you are a regular listener you know at the heart of this series we explore the feminine or female experience and the ways it illuminates through the hands of the artist through visual expression. The dominant resource I used for this episode—and I so grateful for it, is “Pamela Colman Smith: The Untold Story” by Stuart R Kaplan, full of illustrations and photographs, the text includes contributions by scholars like Mary K. Greer. I will add a link to this resource in the podcast show notes. I highly recommend you either add it to your private collection or borrow it from your library.

Smith was born in London to a Jamaican mother and British father. She traveled widely, spent part of her youth, about seven years, in Jamaica and educated as an illustrator at Pratt Institute in New York. She did not graduate, however, from Pratt Institute to help care for her ill mother. Smith was an irrepressible spirit and she deviated from the expectations of women of her time. She pursued career, did not marry or have children, surrounding herself with “like-minded female friends and companions.” These choices to live an independent life as we shall see became a struggle for Smith to those “who did not understand her and who had a hard time positioning her within existing gender, class” By defying conventions, Smith blazed a path for female artists. The women’s magazine The Delineator from the 1912 edition, profiling Smith, wrote: “Before she was twenty she was an inspiration to American Women painters who were working toward something different…..she was the pioneer who gave them courage.” Smith also struggled with the perception of her racial origins. People who met Smith were uncertain about her exact racial make-up. As we shall learn, these biases may explain her lack of sustained success in her artistic and publishing pursuits.

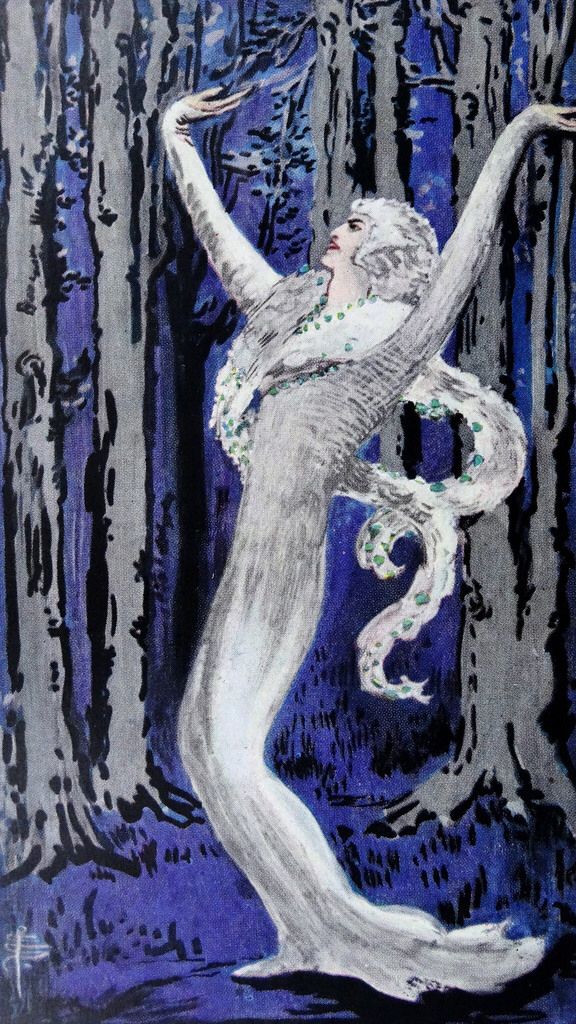

Smith openly and boldly resisted conformity in her life and vividly in her illustrations. Influenced by her work in theatrical design, Smith created compositions that come to this “truth” –to openly, share ideas visually. This is paramount in her prolific work. Her works illicit the attentions of notable contemporary writers like Bram Stoker, best known for the gothic novel “Dracula” and poet William Butler Yeats—she made illustrations for both writers’ published works. Let’s look more closely at an example from her collaboration with Bram Stoker. Smith created six color illustrations for the author’s 1911 novel and horror story, “Lair of the White Worm.” .The central character, Lady Arabella “has the ability to transform into a serpent who wreaks havoc on all she encounters.” In the illustration titled “Lady Arabella was dancing in a fantastic sort of way” we see Arabella with outstretched arms—they extend upwards creating a long, lithe line from her open palms down the outlines of her figure tightly wrapped in a winter-white gown that flairs at her feet. A glamorous fur wrap floats around and behind her like a serpent; alluding to “Worm” in the novel’s title, “Worm” took on a different meaning from what we think of as a “worm;” it was an adaptation of the Anglo-Saxon “wyrm” meaning a dragon or snake.” Even the shape of Lady Arabella’s facial profile, her white hair is closely coiffure like a cap has a “serpent” like feel. Behind the dancing Arabella, we see a grove of bare trees against a purple sky.

I searched for the passage that accompanied Smith’s illustration: Allow me to read it—and as I do, think about Smith’s composition of the woman, Arabella, “dancing in a fantastic sort of way.” Adam is Adam Salton the main protagonist of Stoker’s novel, a 27 year old wealthy Australian who was invited to central England by his grand-uncle Richard Salton, an heir to Lesser Hill.

Round the roadway between the entrances of Diana’s Grove and Lesser Hill were many trees with tall thin trunks with not much foliage except at the top. In the dusk this place was shadowy, and the view of anyone was hampered by the clustering trunks. In the uncertain, tremulous light which fell through the tree-tops, it was hard to distinguish anything clearly, and as Adam looked back, it seemed to him that Lady Arabella was actually dancing in a fantastic sort of way. Her arms were opening and shutting and winding about strangely; the white fur which she wore round her throat was also twisting about, or seemed to be. Not a sound was to be heard. There was something uncanny in all this silent movement which struck Adam as worthy of notice; so he waited, almost stopping his progress altogether, and walked with lingering steps, so as to let her overtake him.

Smith brings to life the mysterious qualities that linger in Lady Arabella’s movements and body. What is notable is the illustration does not include Adam—his impressions of her are instead articulated through Stoker’s prose vs. a visual narrative.

Let’s pause here for a moment and pedal back to Smith’s practice—the way her imagination strolls atop the page with this ethereal quality, transforming our looking experience. What is fascinating to me, what I learned in my research, is one of the contributions of Smith’s synthesis between imagination and image is a neurological condition called synesthesia. Synesthesia occurs when one sense is activated, another unrelated sense is activated at the same time. For Smith, she had the ability to convey music in a complex visual image. “Smith’s ability to visualize music she hears is one of the most important keys to her artistic ability.” Smith created “music pictures.” The French critic G. Jean –Aubrey observed Smith and described the process in this way. Passage from the Kaplan text:

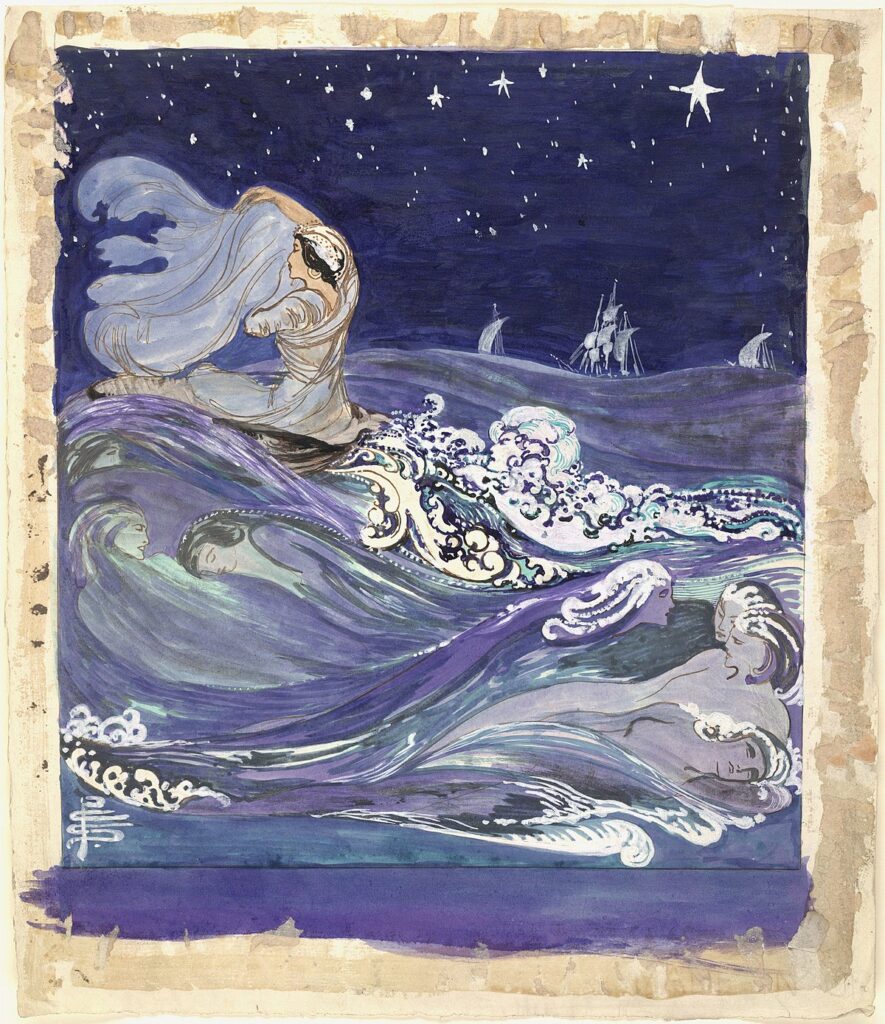

“She comprehends music visually, whether a symphonic piece or a piano composition. For her the musical impression is immediately transformed into a graphic image. I have seen her curled up in a corner in a concert with her sketch book on her knees, a sepia brush in her hand, listening to the work, following the rhythm and smiling, working without haste, as if she had the time to put down her impressions in a few seconds, the page is scarred, caressed, scratched.” The musician Claude Debussy, a friend of Smith, said her drawings to his compositions were his dreams made visible. Smith explained them: “They are not pictures of the music theme, they are not conscious illustrations of the name given to a piece of music, but just what I see when I hear music—thoughts loosed and set free by the spell of sound.” This is relevant to her overall artistic life because it brings to her imagery, to her illustrations something more mystical. These music fueled visions “transcended the logic of space, time and the normal limitations humans usually experience.” Smith in a 1908 article in Strand Magazine likened her visions to “unlocking the door into a beautiful country” peopled with a range of fascinating characters from land and sea.” Let’s journey through one of her music pictures. In the work “Sea Creatures,” an original watercolor from 1904-05, we see in vibrant purples a veiled human woman riding the crest of a wave, followed by several female water spirits. The sky is deep blue with animated, white stars. The waves swirl white foam as the reclined water spirits flow in and up the water waves. The human woman is wrapped in flowing veils that float in the wind. There is this delicacy and femininity that floats through the whole image. It is so enchanting.

With that deeper understanding of Smith’s practice and visionary works, I want to take you along on an encounter Smith had with the New York famed photographer Alfred Stieglitz. He brought a relatively unknown artist, at least for a time, into the limelight. Special thanks to the Yale Art Gallery for this resource. Smith came into Stieglitz’s gallery at 291 Fifth Avenue and asked him to look at some of her drawings and watercolors. She was just 28 years old. Stieglitz was favorably impressed by her youth, exotic appearance and her unusual art. He decided to show her work because he thought it would be “highly instructive to compare drawings and photographs in order to judge photography’s possibilities and limitations.”

In January 1907 he exhibited 72 of her watercolors. Smith was the first painter to have an exhibition in what, until then, had been a gallery devoted exclusively to photography. Though the exhibition was lightly attended, the New York Sun review by the well known music and art critic, James Gibbons Huneker was full of praise. He wrote, “Pamela Colman Smith is a young woman with that quality rare in either sex—imagination.” So let’s look at a couple of the works to see for ourselves this “imagination,” this female voice.

“Death in the House,” an image from “ChimChim: Folk Stories from Jamaica,” 1905. What we see in the background of the image is a liquid black wall with a doorway, open, no door, just beyond is a bright red land formation, along its coast, blue body of water.? At the top of the black wall are two diagonally placed cylinders or pipes, mostly black, delineated with a row of beige lines highlighting the rounded form. There is figure between the two pipes, we see a head, arms and feet curl and brace the pipe as if holding on tightly, perhaps in fear of the deep fall below. In the foreground atop a beige floor, a figure, in a large overcoat, head is bare, I am unsure of the gender, there is a sack by the figure’s side, full and lumpy, cinched at the top. A quote accompanies the image, “Annancy is you comin’ down?” The critic Huneker called the painting “absolutely nerve shattering,” and said that not even the painter Edvard Munch (he is the artist known for The Scream) “could have succeeded better in arousing a profound disquiet.” What is conveyed is this sense of horror through suggestion. Huneker also compared her to William Blake, stating she belonged to the “favored choir” of Blake and his mystics. Stieglitz was equally pleased, remembering, “The exhibition created a sensation..it brought the Whitneys and Havemeyers, Vanderbilts, all classes of people into these tiny rooms of ours.” The majority of the pictures from the collection sold. The 291 Gallery show was quickly followed by one at the Pennsylvania Academy in Philadelphia.

The success emboldened Smith to write a brief manifesto in support of American artistic freedom. Entitled “A Protest Against Fear,” published in March 1907, Smith wrote: “It seems to me that fear has to hold of all this land. Each one has a great fear of himself, a fear to believe, to think, to do, to be, to act. Who dares to do anything without fear of what some others will think or say? How can a country have a living, growing art when it is so bound down by fear, the most dreadful of all evils?” Smith implores artists, art students to resist conformity, to, as I noted at the top of the show, “look inside to create art that comes out of truth and helps share experiences and ideas.” Does not what she wrote over 100 years ago, apply to creatives today? She speaks to each of us.

Smith continued to forge her own path creating and editing. Smith launched the Green Sheaf from 1903-04 and after its demise ran the Green Sheaf Press which focused on women writers. She was also involved with the Women’s Suffrage movement, as an active member of the Suffrage Ateleier creating multiple posters and cards. In Part 2 of my exploration of Smith, we will focus on her legacy as the illustrator of the Rider Waite Tarot deck. In her artistic life, Smith realized minor successes. In her Memoriam, it was noted that the illustrator became “disillusioned with commercial publishers who rejected more of her work, forcing her to self-publish or to publish in collaboration with her literary friends.” Though events like the Stieglitz exhibition turned in her favor, praise from critics and the sale of the prints did not sustain to a more profitable career. Even after her commission of the Rider Waite tarot deck, sales slowed, rejections deepened. “Her disillusionment reached a climax in 1914 when she confided to a friend that she didn’t care for people anymore.”

A published poem, “Alone” provides insight to her isolation and despair.

Smith eventually after suffering from physical and financial decline, moved Cornwall, England where she died penniless and obscure. What is heartbreaking is “no obituary appeared in any local newspapers. Her grave site, if one exists, remains unknown.” She died disappointed of her failure to achieve success yet she never stopped believing in herself. She would all be forgotten except for the 78 tarot paintings known as the Rider Waite Tarot pack. And those cards, that deck, the imagery touches the hearts and emotions of millions of people today. For me personally, we cannot change Smith’s biography, but we do have her prints, her works, her writings, the imagery—we can bring awareness and celebrate her and allow her imagery, her narratives to transform us lives and spirits.

I want to end this episode with Smith’s words, laced with her indomitable spirit. She composed a letter advising art students, published in The Craftsman. She writes: “Learn from everything, see everything and above all feel everything. And make other people when they look at your drawing fell it too!…Banish fear, brace your courage, place your ideal high up with the sun, away from the dirt and squalor and ugliness around you and let that power enter into your work—energy, courage, life, love. Use your wits, use your eyes. Find eyes within look for the door into the unknown country. Ride on your quest—for what we are all seeking—Beauty. Beauty of thought first, beauty of feeling, beauty of form, beauty of color, beauty of sound, appreciation, joy and the power of showing it to others.”

Getting to know Pamela Colman Smith through this podcast, I feel such a kindred spirit with her. I adore her, her imagery presses into my mind, my spirit, my imagination, to see the world, to see beauty through her lens, my heart just soars.

I look forward to sharing with you part 2 of my celebration of Pamela Colman Smith. Thank you for listening. Resources for this episode are listed in the podcast show notes. I dedicate this episode to three women who work tirelessly in creating arenas for women artists to be exposed, to navigate, to connect their works, their feminine voices, with collections and collectors so women artists can achieve the successes they deserve. Special Shout Out to Liezel Strauss from Art Girl Rising, Hall Rockefeller, Less than Half Salon and Kelly Groehler from Alice Riot. Links to their websites are also in the podcast show notes so you can learn more. Thank you!