A two-part episode, join me in an exploration with Digital Art as a practice and medium. This episode dives into Digital Art as a medium through four categories or themes; installation, film, video and animation, Virtual Reality, Sound Environments. In part two, we will journey into artists who use digital art as a means of expression. I speak with emerging New England artist Ande Ja Johnson and take a close look at the Digital Collagist Eugenia Loli.

Resources include:

Paul, Christiane. “Digital Art.” London: Thames and Hudson, 2008; writers Penny Rafferty, Molly Gottschalk, Oliver Grau, Dr Karen Leader, Sarah Urist Green of the Art Assignment and the Tate Museum, Brooklyn Museum and Museum of Modern Art.

Special thanks to this episode’s sponsor: Nine 90 Branding. Follow on IG @nine90branding

Works highlighted include:

Script: Episode 159: Two Part Mini-Series: Digital Art

First a shout out and my gratitude for Beyond the Paint podcast sponsor Nine 90 Branding and Design for your business presence. Thanks Dan, the creator of Nine 90 Branding for your support! I am so excited to explore with you aspects of Digital Art as a practice and medium in two episodes, a little mini-series. Today, we will look at Digital art as a medium and in part 2, a journey into artists who use digital art as a means of expression. We will look at David Hockney who employs the IPad, a local Connecticut emerging artist, Ande Ja Johnson who uses computer software to create portraits, and Digital Collagist, contemporary female artist Eugenia Loli.

Digital art, once called computer art or new media art refers to art made using software, computers, or other electronic devices. Anything produced or made on digital media, such as animations, photographs, illustrations, videos, digital paintings, and such can be classified as digital art. From the writer Robert Atkins, “Western artists have always responded quickly to new materials and technologies; consider the rapid replacement of egg tempera by oil paint in the 15th century Netherlands.” Artists have seized on the computer as a tool since the mid-1960s, embracing the debut, around 1980, of so called paint systems-interactive, real time painting programs that mimic the non-electronic use of brushes and palettes, like Photoshop.

One ongoing debate regarding digital art is does it count as real art? If by real you mean is the end product actual physical items made using physical tools? Then no. But digital art is “Real” because it requires creative techniques, skills that traditional art needs. Traditional art media includes paint, sculpture, graphite for drawing, etc. It can be argued digital art requires the same amount of skill, talent, originality, knowledge, effort as any other traditional art piece. “Art is art, and the primary purpose of art is to express the artist’s emotions regardless of the medium used. Most artists who employ digital technology think of themselves simply as artists, rather than computer, digital or electronic practitioners. (show Amy Image)

As a primary resource for this episode, I referenced the text Digital Art, by Christiane Paul alongside other resources—you will hear me quote often. So let’s dive in. “As an artistic medium, the artist uses digital platforms from production to presentation.” The output of the work is difficult to categorize because “the art itself has multiple manifestations and is extremely hybrid. The work can present itself “as anything ranging from an interactive installation to virtual reality, to software written by the artist or any combination thereof.” Ultimately every object, even the virtual one—is about its own materiality, “which informs the ways in which it creates meaning.” Let’s consider and explore “forms of digital art” I am going to highlight in this episode Installation, Film, Video, Animation, Virtual Reality, and Musical Environments.

Installation Art: exists in and establishes a connection to a physical space. Installations create an environment that can entail varying degrees of immersion. From CBC Arts: “Installation is made of many elements that have a relationship to each other to make a larger point or build a story. Rather than the specific object being independently important, it’s the relationship between all of them that creates meaning. It creates an immersive experience. Immersion has a long history and is inextricably connected with art, architecture: prehistoric cave paintings are considered early immersive environments, Gothic cathedrals, one element is stained glass windows. They bathe the cathedral in colored light, enlivening and invigorating the space, creating an ethereal atmosphere of transformation for the congregant, for the faithful. (photos of cave, church)

One female artist that used installation as a medium: Judy Chicago: The Dinner Party. An icon of 1970s art, the Dinner Party comprises a massive ceremonial banquet arranged on a triangular table with a total of 39 place settings, each commemorating an important woman from history. Each setting consists of embroidered runners, gold chalices and utensils, and china painted porcelain plates with raised central motifs that are based on the vulva and butterfly forms and rendered in styles appropriate to the individual woman being honored. The names of another 999 women are inscribed in gold on the white tile floor below the triangular table. Panels accompanying the art provide further information on the women honored. The Dinner Party makes the point there have been many women in history, even if history has chosen to ignore them. As the audience or viewer moves around the table, viewing this assembled community of women, viewers participate in the joy of women’s heritage, but also in the realization “this heritage has been obscured, fragmented, and denied for so long.” Two of my favorite settings celebrate the poet Emily Dickinson and the 16th century painter Artemisia Gentileschi. (photos, dinner party, Emily Dickinson setting and portrait, Gentileschi setting and portrait)

The Dinner Party is composed from tangible materials, ceramics, tile, textiles. A digital installation that is both interactive and immersive, from the collaborative “teamlab, an interdisciplinary group of various specialists such as artists, programmers, engineers, CG animators, mathematicians and architects. They explore the relationship between the self and the world. Their 2017 work, “Flowers and People, Cannot be Controlled but Live Together—Transcending Boundaries, A Whole Year per Hour” is a fascinating immersive installation. The spectator enters the space. Surrounding them on these multiplex screens for over a period of one hour, we become immersed in a year’s worth of seasonal flowers and blossoms. Flowers are born, grow, bloom and eventually scatter and die. The cycle of birth and death repeats itself in perpetuity. If people stay still, more flowers are born. If people touch the flowers and walk around the space, the flowers scatter all at once. The artwork is not a pre-recorded image that is played back; it is created by a computer program that continuously renders the work in real time. The interaction between people and the installation causes continuous change in the artwork; previous visual states can never be replicated, and will never reoccur. The picture at this moment can never be seen again.

Film, Video and Animation—digital moving image, the medium has “affected and reconfigured the moving image in various ways and areas.” In this category, I am going to focus on Video art as a medium. It is often site-specific, and can be installed, exhibited, viewed and recorded in different places. Video art originated in 1965 when the Korean born artist Nam June Paik explored its potential with the new portable video recorder, Sony camera. It was battery operated and self contained, the camera and recording system could be operated by a single person (art assignment) Paik collaborated with cellist Charlotte Morman on his TV Cello where Morman performed by running her bow across a stack of TVs that played prerecorded images of her playing the cello. The internet has allowed video art to be shared far and wide but also to exist within and through online platforms. Difficult to define, “video art is a catch all term describing a moving image captured on magnetic tape or in digital format. From the curator Sarah Urist Green from the Art Assignment asserts the word video comes from Latin meaning “I see” and in the way it reflects how we understand and see and process the world, it works well enough. (photos: Paik TV cello)

In my preparations and research for this medium, I was so moved by the Belgium, female artist Chantel Ackerman. Her 2015 work “No Home Movie,” focuses on a conversation between Ackerman and her mother Natalia, a Polish immigrant who was a survivor of Auschwitz, before her death at 86. “It consists of conversations in person and over Skype over several months. Akerman whittled the recordings down around 40 hours of footage to 115 minutes, using small handheld cameras and her Blackberry to film. Akerman said, “I think if I knew I was going to do this, I wouldn’t have dared to do it”

Punctured in between their conversations, momentary eruptions of pain, poignancy, “You were the most beautiful mother; I was always proud when you picked me up from kindergarten,” there are long shots of barren landscapes and domestic nothingness. Writer Tara Brady asserts so poignantly, “Its absences and deadness is precisely the point. No Home Movie may be intimate and domestic but it’s not a home movie because there is no more home. (photo: No Home Movie)

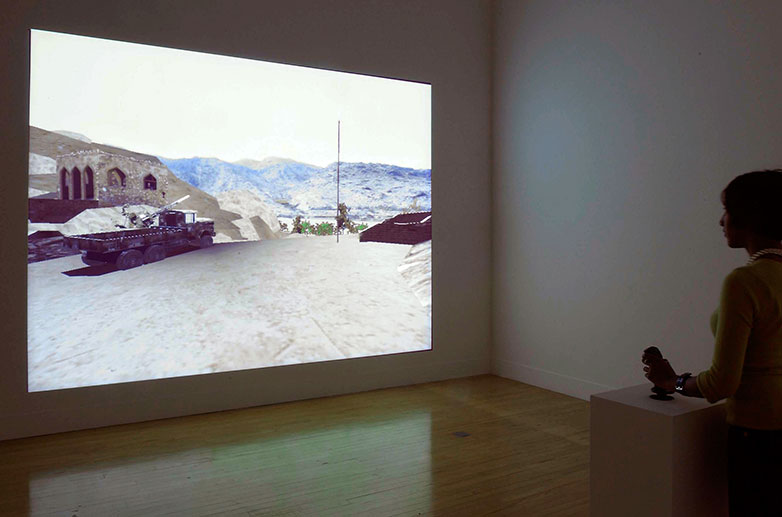

In the category Virtual Reality, from the writer Penny Rafferty at the Tate Museum defines Virtual Reality as a technology that enables a person to interact with a computer-simulated environment, be it based on a real or an imagined place. The computer scientist Jaron Lanier popularised the term virtual reality in the early 1980s. Virtual reality environments are usually visual experiences, displayed on computer screens or through special stereoscopic displays. Some simulations include additional sensory information such as sound through speakers or headphones. One example of an earlier exploration into virtual reality is from 2003 and the duo Langlands and Bell, Ben Langlands and Nikki Bell, collaborators since 1978. Commissioned by the Imperial War Museum in London, they created a virtual reality tour of Osama Bin Laden’s hideout in Afghanistan and audiences were invited to navigate the building using a joy stick. “The House of Osama bin Laden” is a trilogy of artworks in the form of an interactive multimedia installation made by the artists following a research visit to Afghanistan in October 2002. Their purpose was to explore the aftermath of September 11 and the western intervention in Afghanistan. On their website, which I will include in the podcast notes are several photo still and a projection of the computer animation for you to view. In one of the stills you can see a spectator or viewer in a gallery space with joy sticks in hand move through the different spaces of the hideout. The artists describe the work, “We see ourselves as artists who visited a war zone while researching a commission titled, “The Aftermath of September 11 and the war of Afghanistan.”

Another early pioneer using Virtual Reality as an artistic medium is Rachel Rossin, a self-taught programming whiz who began coding at age eight. From her 2015 work “I came and went as a ghost hand,” the writer Molly Gottschalk describes the experience: “Strapping the Virtual Reality headset tightly to my head. Suddenly I’ve left the building ]. Up a staircase I float, weightlessly, into a baby blue world littered with the frames of burnt-out buildings and fragments of the artist’s memories—vignettes of her home and tiny studio, a mini-fridge here, a laptop there, so real that I try to grab them with my hand. Jaw agape, I look up, down, behind me; each time, the imagery tracks with my line of sight. I wince my eyes the first time I traverse a wall, duck my head as I move through a roof. For two-and-a-half minutes, I no longer feel the wooden, paint-splattered floorboards beneath my feet. The last category to explore with you my listeners: Sound and Music Environments

Mexican multimedia artist Erika Harrsch creates, along with traditional media pieces, visceral multi-media experiences which question the status quo on national identities, humanitarian aid, immigration reform and self. ‘Under the Same Sky… We Dream’ is a particularly moving, interactive, digital art installation. Her sound installation in collaboration with singer Magos Herrera. This piece is intended to immortalise the journeys of immigrant Mexican children as they migrate to America seeking solace, and to question why they are often imprisoned whilst on their search for safety. In this installation a continuous 24-hour time lapse of the sky crafted by Harrsch from 35,000 photographs plays on a screen that mimics the Mexican-American border, while a haunting sung soundtrack of the Dream Act Bill of Congress plays. Around the room mattresses and metallic refugee blankets are haphazardly placed along with copies of Harrsch’s book Dream. The whole effect of this scene is contemplative, jarring and vital; Harrsch urges exhibition visitors to confront the bleak realities faced by these ‘dreamers’ who despite their youth, and faced with mounting hostility and uncertainty as they hope for a new life across the border.

The idea of be immersed in art through our senses, physically surrounding us on all sides with visual imagery has a long history. From the art historian Oliver Grau, “Consider the frescoes covering all four walls in a room in the Villa dei Misteri at Pompei, Italy created about 60 BC It drew observers in to a 360 degree depiction of the preparations for a cult ritual. Or the adorning rooms in Livia’s Villa at Prima Porta dating from about 20 BC creating the illusion of a lush and verdant garden. From 1343, the frescoes in the Chambre du Cerf (Chamber of the Stag) at Pope Clement VI’s palace in Avignon, France place the observer at the centre of a hunting scene.

Peepshow boxes first appeared in the eighteenth century, and in 1787 Robert Barker patented his hugely successful process for producing panoramic views on circular canvasses in correct perspective for observers standing at the centre. The techniques of cinematography and computing simply extended the opportunities for artists to immerse observers in an illusory world.”

I hope this episode offers you a window into the “limitless unbounded ability,” digital art as an artistic medium, has to create visual worlds. “Worlds that reflect back to us the world we live in. Digital art is a vessel of creation that should be embraced. Dr. Karen Leader said, “All the terms that you can apply to other art forms can certainly be applied to digital art: complexity, thoughtfulness, craft, originality, research, style.” said Dr. Leader, “The key is not so much the medium as it is what is brought to that medium.” My hope for you is that you explore and journey into this artistic medium, digital art. At my website, beyondthepaint.net I included most of the works highlighted including web links to the creators. Part 2, exploring two female artists, including an interview with the emerging digital artist Andje Johnson. Thank you!