Ann Stoddard is a contemporary interdisciplinary artist, a feminist and an environmentalist. Her work, practice coupled with social activism engage with nature, from rivers in and around Maryland to Corn Fields and beyond. This episode includes some historical perspective of female, pioneer ecofeminists and a lively conversation with Stoddard.

Resources for the Episode include:

Ann Stoddard website Stoddard is represented A.I.R. Gallery

Art in America (May 2020) Eleanor Heartney, “How the Ecological Art Practices of Today Were Born in 1970s Feminism”

Packard, Cassie. “Ecofeminist Art Takes Root,” July, 2020

Cover Image: Ann Stoddard Studio-Ann Stoddard website

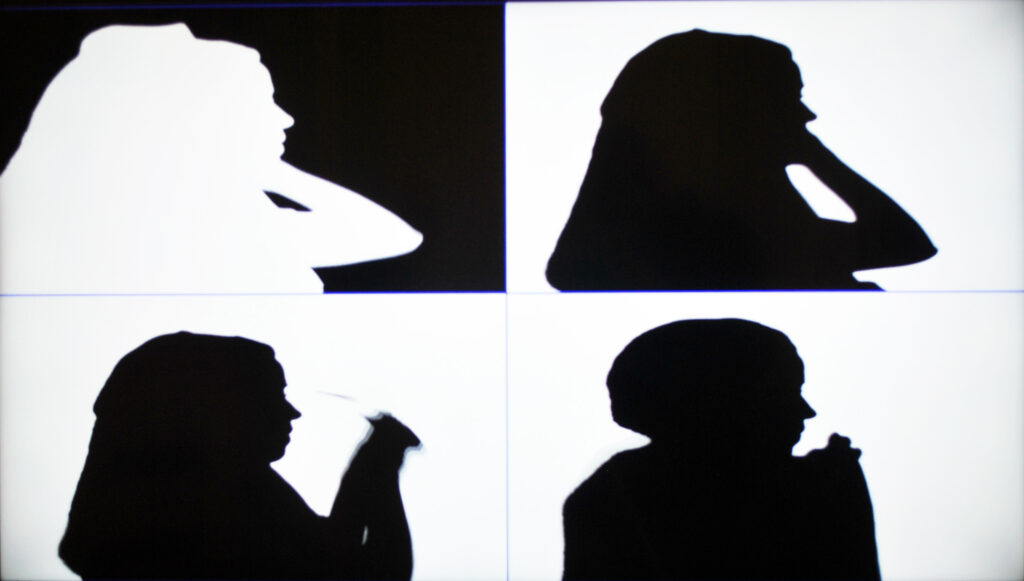

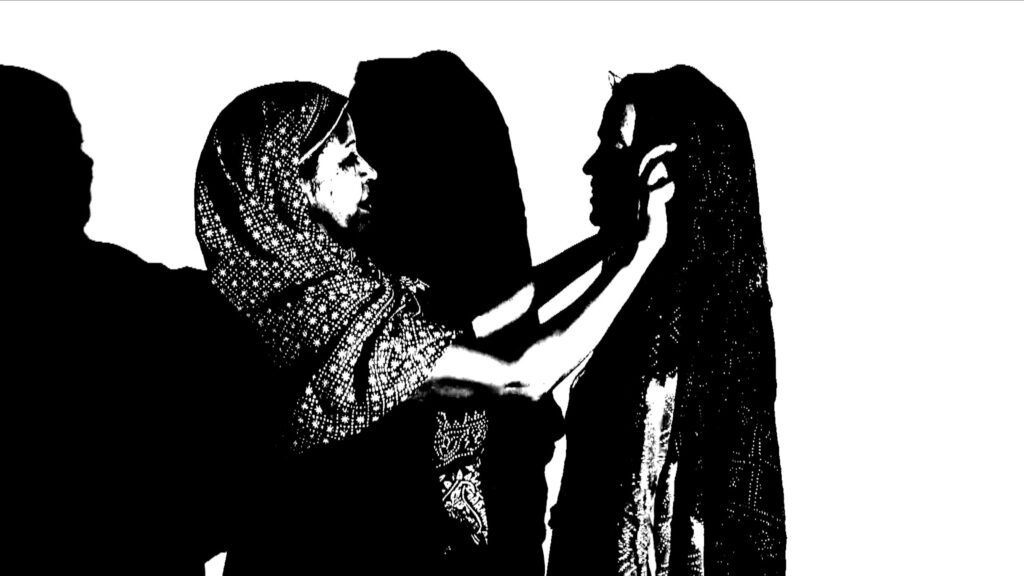

“Seeing Things Headscarf” and “Sisterhood: Shared Threads” Video Still Image

Script:

Ann Stoddard is a contemporary interdisciplinary artist, a feminist and an environmentalist. In her practice and works, Stoddard joins hands in collaboration with Mother Earth.

Before we journey into two of her works and installations, let’s consider female artists whose work and practice is centered on environmental issues. Another term is Ecofeminism. What is Ecofeminism? From the scholar Mary Mellor and her text “Feminism and Ecology,” “Ecofeminism is a movement that sees a connection between exploitation and degradation of the natural world and the subordination and oppression of women. Named in the late 1970s when the French feminist Francoise d’Eaubonne coined the term, Ecofeminism emerged alongside second wave feminism and the green movement.

It recognizes that life in society as well as nature should be maintained by means of collaboration instead of domination — and that the domination of women and nature stem from the same roots. And that the fight for women’s rights is connected to the fight for a more sustainable world. Since then, many Ecofeminists have raised their voices to present the connection between these two struggles. It is important to note that Ecofeminism did not exclude men. Ecofeminists echoed ideas expressed as well by such visionaries as the famous naturalist John Muir and the futurist Buckminster Fuller.

Betsy Damon is one pioneer Ecofeminist. Damon’s art practice “embodies a stark philosophy.” Damon explains: “Nothing is worth saying unless it acknowledges interconnectivity.” In the 1970s the artist put on interactive street performances in New York; for example in the performance piece “Blind Beggar Woman,” Damon “crouches over a begging bowl and asks passersby to share stories.” In connection with Mother Earth, Damon “cast 250 feet of handmade paper pulp of a riverbed in Castle Valley, Utah; Titled, “The Memory of Clean Water,” (1985) the sculpture climbs the gallery walls and spills onto the floor. The surface is pockmarked with small holes; it is multi-colored, fragile yet massive. It was through her work in traditional art that Damon “realized she wanted to create work with a more direct impact on the ecosystem. Water is celebrated as a living thing, a source of life, and a foundation of health. Her work and practice signifies a moment of reckoning towards activism. Her work led her to form in 1991, Keepers of the Waters that serves as an umbrella for her diverse activities.

Her projects extend beyond “art,” and involve a wide-ranging education effort. One example is the clean-up of the Mississippi River with a focus on taking down dams, restoring water flow and reconnecting small creeks and rivers.

Agnes Denes: a New York based artist who was also deeply involved in the feminist community in the 1970s. A member of the Ad Hoe Women Artists’ Committee which pressured museums to show more art by women; she was also a founding member of A.I.R. gallery, the first women’s co-op gallery in the United States, who my guest today Ann Stoddard is a current member.

Her iconic work from 1982 is “Wheatfield,” site specific, Denes planted on two acres of soil that had been excavated to build the World Trade Center. In a photograph we see yellow wheat swaying before Manhattan skyscrapers. The juxtaposition of “Wheatfield” against a horizon of skyscrapers “serves as a reminder that even the mightiest urban system could not survive without the ancient art of agriculture.

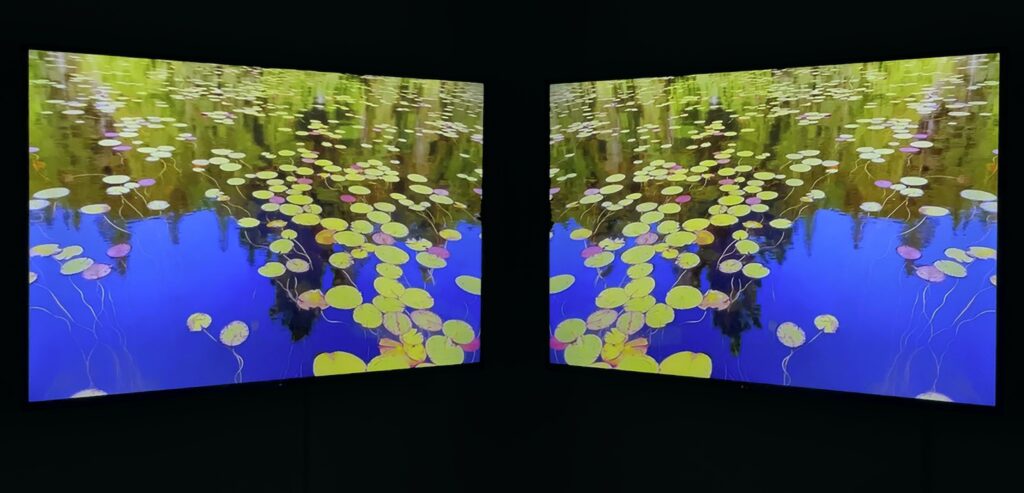

Let’s shift to my guest the contemporary artist Anne Stoddard and the work “Waterlilies: Madawaska River.” I experienced this work at the A.I.R. gallery in the exhibition Structures of Feelings. Before the viewer are two screens, equal in size, installed in the corner of the gallery space. From each screen we experience the same running scene, a close up view of a river, the sun streams creating lively reflections in the water. We see its natural vegetation; water lilies. Stoddard who we cannot see is in a canoe recording the scene. The entire scene is filled with delightful, calming views of the water lilies, including underwater views of their stems—the sound of the slap of the canoe paddle on the water. In the curatorial essay from the exhibition, the curator describes the “mirrored reflections of trees on the shoreline and by the river current as a “disorienting sense of circularity.” For me, I became immersed in the images, the rhythm, the sounds; reminded me of the monumental Monet paintings of water lilies; the sense of water lilies peacefully floating within the sun’s soothing light.

Another video performance work is “Corn Walk.” This piece I experienced online on Stoddard’s website. It is about a ten minute work, consisting of two mirror videos (left and right) on flat screens in a corner installation. Stoddard records walking through a dense corn field; She navigates a path of sturdy green husks and leaves, we are keen to the sounds, her body brushing against the leaves, thick stems, crunching, whishing, from time to time she scans her camera, looking for perhaps an opening to continue her journey; she moves somewhat intuitively, the unfurled leaves of the corn stalks pointedly become her guides. Unlike September in Madawaska, Corn Walk is “loud,” “noisy,” you can sense her body’s exertion as she pushes through and at one point, the camera casts downward—we see the bright pink of Stoddard’s athletic shoes, a jolt of color against the brown dirt ground. At the end of the video, Stoddard exits the cornfield, stepping into an open area of green grass, her camera spans upwards towards white billowing clouds suspended in the bluest sky.

Like the pioneer Ecofeminists, Stoddard is an activist. She developed and taught the first courses on the History of Women Artists at Indiana University. During her tenure she also organized a three day workshop and lecture critique by Judy Chicago. Stoddard co-founded and lead a NOW chapter in Bloomington Indiana. Her feminist activism continued in Washing DC, as the co-founder and leader of a chapter of the Women’s Caucus for Art. She co-curated an exhibition of works by women with the National Women’s Caucus for Art at the University of Maryland Art Gallery. In her series, “Speech and Hearing,” consisting of paintings, drawing and lithographs, Stoddard challenges sexist stereotypes. That is just a partial list of her work, practice and like Betsy Damon, employing her activism and art within the broader community. Please join me now to hear from the artist herself in my conversation with Anne Stoddard.